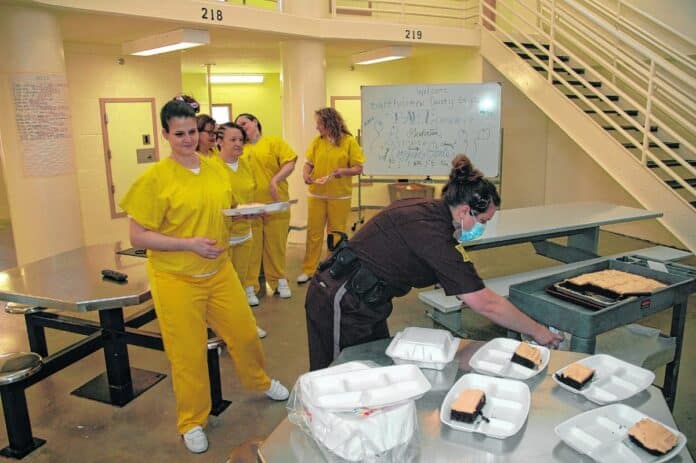

A significant milestone was achieved when five women became the first class to graduate from a new addiction treatment program inside the Bartholomew County Jail.

Sunshine Johnson, Kimberly Kirk, Amanda Spencer, Kenya Jones and Mika Reynolds marked the six-month achievement by celebrating with jail correctional staff, administrators and mental health professionals at the Bartholomew County Sheriff’s Department.

“We are very proud of these five ladies,” Chief Deputy Sheriff Maj. Chris Lane said. “It was a lot of work, and quite a test of their individual characters to finish the program.”

Another milestone will be reached right before the Independence Day holiday weekend, when six men graduate from the same program. That class began their program on Feb. 10, Lane said.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

When the women’s program began in January, participants received group therapy up to five days a week for as long as four hours a day, Lane said. When the program for men began a month later, each group received the same type of counseling three days a week, he said.

All five women who graduated Friday said they had been addicted to heroin, methamphetamine or a combination of both, Bartholomew County Jail Addiction Treatment Coordinator Theresa Patton said.

Spencer, 39, described the intensive program that she and others began on Jan. 13 as “absolutely tough” — especially with the arrival of COVID-19 pandemic in early March.

“It really put a damper on the situation, and what we were trying to do with our programming.” Spencer said. “We really had to pick up with the skills we have been taught, and go with what we knew to go through this as a group.”

Any attempt to rush the program can be counterproductive, Patton said. It takes a number of months for those in recovery to regain their ability for rational reasoning, she said.

But the good news is that if a therapist lays out what is expected, meets the individual where they are, and begins to educate the person, the individual is bound to change, she said.

Two therapies

Combating heroin and methamphetamine addiction often requires two forms of therapy, Patton said.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, in which negative patterns of thought about the self and the world are challenged in order to alter unwanted behavior patterns. This therapy is also effective in treating mood disorders such as depression.

Dialectical behavioral therapy, which is a psychotherapy that begins with treating borderline personality disorders. It is also useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal thoughts, as well as changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance abuse.

Patton was able to break down past incidents, and match it with each individual’s current behavior, allowing those in treatment to pinpoint causes for their addiction, Spencer said.

Jail and addiction specialists lauded the city and county for jointly funding this program, as well as other services. But nobody had greater praise than Spencer for the partnership formed between the Columbus City Council, Columbus Regional Hospital and the Alliance for Substance Abuse Progress (ASAP).

“… I never thought anything like this would be possible,” Spencer said. “If it weren’t for (city and county government, as well as ASAP) working together, we wouldn’t have been able to do it.”

Johnson, 33, admits that when she started the program in January, she was feeling anxious and a little frightened.

“When you are still in the grasp of addiction, and you still have that mindset of failure, its a little nerve-wracking,” Johnson said. “But once I got used to the idea, it was like all of my desires were to create a better future for myself. Then, I just did it. It was awesome.”

After completing the program, all five participants now feel strongly motivated to abstain from narcotics and work to make better lives for themselves, Johnson said.

However, the first year of recovery is always the toughest, and the women must advocate for themselves if they wish to avoid a relapse, Patton said.

Since all the women are still incarcerated, they will be required to move on to different phases of treatment advocated by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), Patton said. That includes outpatient care, after-care and possibly residential care. f the entire ASAM steps are followed, the treatment should last about nine months for each inmate, Patton said.

But the final ASAM phase — residential care — is the most difficult to obtain. Most treatment programs in Indiana don’t explore a recovering addict’s needs such as housing, financial, vocational, educational, legal, transportation or child care services, Patton said.

“It creates a revolving door,” Patton said. “(Recovering addicts) are going to go back to what they know, because their new behavior hasn’t been cemented yet.”

Brighter future

But through programs and services offered through ASAP and Centerstone Behavioral Health, those in recovery may soon be able to provide a thorough support system to get them through the toughest times, she said.

Every phase will allow individuals to test theories they’ve learned, practice behaviors they were taught, and try things out they learned during treatment in the real world, Patton said.

If graduates such as Johnson and Spencer can advocate for themselves and keep off drugs for at least a year, they may be allowed to mentor others in recovery at the jail, Patton said. If they keep off drugs for two years, they might be considered a sponsor capable of providing peer recovery coaching, she said.

Although she realizes that money will be tight next year due to a bad economy, Johnson says reducing funding for the jail’s addiction treatment program would be a mistake.

“I’m telling you, this is going to be a success, and that is already showing,” Johnson said. “If we can get addicts off the streets and help them, it will clean up our community and give people a future.”

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”A funding request” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

Among the proposals being presented today to the Substance Abuse Public Funding Board today is a request to expand the jail’s drug treatment program.

After the proposal was approved last week by an advisory committee, the board will be asked to recommend almost $250,000 in order to hire three additional addiction specialists: one full-time and two part-time, according to Bartholomew County Chief Deputy Sheriff Maj. Chris Lane.

In addition to putting in nearly 30 hours a week to provide group therapy, jail addiction treatment coordinator Theresa Patton said she’s also giving individual therapy, as well as writing progress notes and maintaining correspondence with courts, attorney, probation officials and representatives of the Indiana Department of Child Services.

It is impossible to maintain or expand the jail’s addiction treatment program without additional specialists, she said. If the funding board votes to recommend the request, it will be taken directly to both the Columbus City Council and Bartholomew County Council for consideration. Most requests are divided between city and county government.

The Substance Abuse Funding Board will meet at 1 p.m. today at Columbus City Hall. The meeting can be watched live on the City of Columbus’ website.

[sc:pullout-text-end][sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”About the program” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

The addiction treatment program at the Bartholomew County Jail is based on six dimensions designed to create a holistic, biopsychosocial assessment of an individual for planning and treatment across all services and levels of care.

The six dimensions developed by the American Society of Addiction Medicine deal with the exploration of:

- An individual’s past and current experiences of substance use and withdrawal.

- A person’s health history and current physical condition.

- An inmate’s thoughts, emotions and mental health issues.

- An individual’s readiness and interest in changing.

- An inmate’s unique relationship with relapse or continued use or problems.

- A person’s recovery or living situation, and the surrounding people, places or things.

Source: American Society of Addiction Medicine

[sc:pullout-text-end]