Restaurants are a huge part of our economy. There are thousands of restaurants employing millions of people serving customers spending billions of dollars.

Restaurants can be small, single locations owned and operated by sole proprietors to publicly-traded, multi-concept companies like Darden Restaurants, Inc. (DRI—concepts including The Capital Grille, Olive Garden, LongHorn Steakhouse, Cheddar’s and Yard House).

The economics for full-service restaurants are brutal, with soaring rents, staffing and food costs combining with low barriers to entry leading to a high failure rate (even among highly-regarded eateries). In addition, “fast-casual” operators like Chipotle Mexican Grill and Panera Bread are attacking from below, and competitors like Blue Apron and Whole Foods (now part of Amazon) are enticing consumers to dine at home.

A full-service restaurant’s staff is divided into “front-” (servers, bartenders and bussers) and “back-” (cooks and dishwashers) of-house. Front-of-house staff interacts directly with customers and can earn significantly more (due to tips) than their colleagues in the back, who also play an important role in the customers’ dining experience (but are typically ineligible to share in tips).

The practice of tipping is ingrained in American culture but is a huge can of worms. Not only does it lead to a huge disparity in income between front/back staff, it perpetuates a class system where the server is subservient and dependent on the kindness and largesse of the customer. I’ve witnessed plenty of abusive customers, and in this era of #MeToo, it’s time for a change.

Restauranteur Danny Meyer, CEO of the Union Square Hospitality Group (whose high-end NYC concepts include Gramercy Tavern and The Modern) and Shake Shack fame is generally credited with the first large-scale no-tipping “experiment” when he decided in 2015 to introduce his “Hospitality Included” model. Briefly, Meyer believed the tipping system was broken and raised menu prices to cover the cost of “the linen, the flowers, the cook, the reservationist, the server, the wine director, the rent.”

It’s too soon to say if the no-tipping experiment will succeed. Others who tried found the change of business model and education of staff and customers too difficult and have gone back to tipping. In fact, Meyer and other high-profile restauranteurs like Tom Colicchio (Crafted Hospitality) and David Chang (Momofuku) have been accused of a conspiracy to rip off customers and workers.

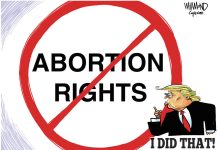

When you leave a gratuity for your server, you have a reasonable expectation that money will go to the server. That’s about to change under a Trump administration proposal. The new Department of Labor rule would allow restauranteurs to pool tips and use them for any purpose, as long as all of their workers are paid the minimum wage, which is $7.25/hour nationally and higher in some states or cities.

This new rule would invalidate an Obama administration rule from 2011, which made tips the property of the tipped employee and not subject to sharing with back-of-the house workers (though front-of-the house staff could pool/share tips). While restauranteurs paying at least minimum wage could reallocate tips to cooks and dishwashers, they could also use the money to subsidize “Happy Hour” or just pocket it.

While this could be similar to “hospitality included,” it’s a fraud upon consumers and could lead to outright stealing of wages from some of the most vulnerable members of the workforce.

Mickey Kim is the chief operating officer and chief compliance officer for Columbus-based investment adviser Kirr Marbach & Co. Kim also writes for the Indianapolis Business Journal. He can be reached at 812-376-9444 or [email protected].