Nothing is new about the corrupting influence of money in politics. It’s been about 150 years since Mark Twain observed, “We have the best government that money can buy.”

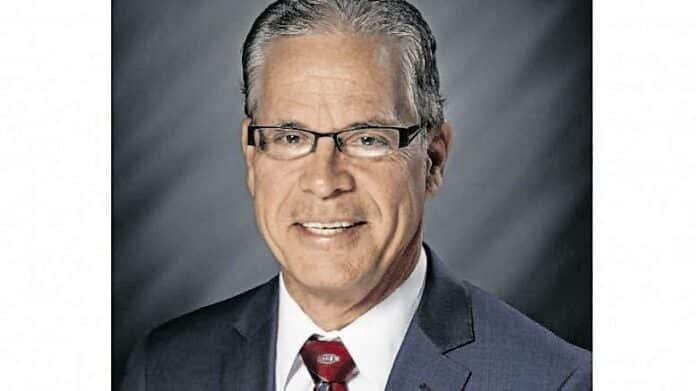

But recent revelations about Indiana Republican Sen. Mike Braun’s campaign money — some of the $19,663,419 he raised to topple Democratic Sen. Joe Donnelly in 2018 — are beneath even the exceptionally low expectations we set for our politicians.

Braun claims everything is on the level with his campaign’s money machine, despite a Federal Election Commission draft report saying he improperly gave more than $1 million to his campaign and, as the Indianapolis Business Journal reported last week, “overstated receipts and disbursements by more than $6 million, and improperly received $1.5 million from Meyer Distributing, an auto-parts distributor owned by Braun that were reported as loans.”

These seem more than simple bookkeeping snafus. They seem like trouble for Braun, if there are any consequences for what look like violations of federal election laws. That’s a mighty big “if” these days.

To be fair, there is much we don’t know about Braun’s money problems. Still, there is much we do know of Braun’s campaign money that raises issues.

For instance, of the almost $20 million Braun’s campaign raised for his 2018 Senate campaign, more than half of it — $11.5 million — was reported as loans, according to the FEC. That is a big red flag. To whom is our junior senator beholden? Furthermore, what entitled him to loans that the FEC says lacked adequate collateral and documentation? (For the record, Donnelly raised just over $17.25 million in his Senate re-election bid, none of which was reported as a loan, according to the FEC.)

Braun blamed a former campaign treasurer when asked to comment about his campaign’s FEC problems. It was someone else’s fault. But Braun needs to accept responsibility here. After all, he directed the company that gave rise to some of the donations and/or loans that appear to have either skirted or outright violated election law.

It’s far too early to tell whether Braun may suffer any FEC consequences from all of this, but politically, it’s damaging. Braun won’t face re-election until 2024, but donors are sensitive to this kind of mess. They don’t like appearing in scandalous headlines.

Meanwhile, the FEC’s inspector general earlier this month issued a report noting the difficulty the commission faces keeping up with ensuring campaigns abide by the law. The top reason? Campaign spending has gone mad. The unrelenting money chase consumes modern politics and modern politicians, does nothing for good government and drives much of the public’s distaste for the entire enterprise.

Consider this: In the 2000 election cycle, campaigns nationwide spent less than $3 billion on federal elections. In 2020, that figure had skyrocketed to $14.5 billion — nearly a five-fold increase in 20 years. Similarly, the number of transactions subject to FEC regulation grew from about 600,000 to nearly 3 million.

And out of all those numbers, Braun’s stood out to the FEC. He owes Hoosiers honest explanations for what appears to be his campaign’s disregard of federal election rules and laws.