Mike Wolanin | The Republic Shoes and electronic candles were on display on the steps of Columbus City Hall before an International Overdose Awareness event in Columbus, Ind., Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021.

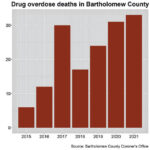

Drug overdose deaths in Bartholomew County rose last year to their highest level on record, deepening a public health crisis that local officials say is now being fueled by the pandemic and a more dangerous drug supply.

A total of 33 people in Bartholomew County died from drug overdoses in 2021 — the third consecutive year that overdose deaths increased and roughly double the number of deaths recorded in 2018, according to updated figures from the Bartholomew County Coroner’s Office.

Overall, there were 153 fatal drug overdoses in the county from 2015 to 2021, roughly one death every 16.5 days.

The increase in deaths has alarmed local officials, who say it reflects the growing prevalence of deadly fentanyl on the streets of Columbus and the “just terrible” impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on longstanding substance abuse and mental health issues in the community.

And they fear that “this is going to continue for the foreseeable future.”

“Unfortunately, I’m not surprised by (the increase in deaths),” said Dr. Kevin Terrell, medical director at Columbus Regional Health’s Treatment and Support Center, or TASC, which offers a range of outpatient treatments for substance use disorders.

“It’s at least two factors — the COVID pandemic, as well as the emergence of fentanyl as a drug of abuse within our community,” Terrell added.

Dying ‘at unprecedented rate’

Fentanyl use has surged across the United States, causing officials to sound the alarm, with the drug now being increasingly laced with other drugs, including methamphetamine and counterfeit pills, because it is cheaper and more powerful, leading to a surge in what officials believe are unintentional overdose deaths.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine that is often illegally produced and sold for its heroin-like effect, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. A fatal dose of fentanyl is small enough to fit on the tip of a pencil, according to the DEA.

In September, the DEA issued its first public safety alert in six years, warning that counterfeit pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine were being seized “in every U.S. state in unprecedented quantities” and “are killing Americans at an unprecedented rate.”

The Columbus Police Department, for its part, said it had seized more than 100 counterfeit Xanax pills containing fentanyl as of this past May.

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report that para-fluorofentanyl and metonitazene — two opioids that are more potent than fentanyl — are being seen more often by medical examiners who investigate overdose deaths in Tennessee, with one official telling The Associated Press that people who use these drugs often “don’t even inject the full syringe” before overdosing.

Fentanyl use on the rise

Locally, officials say they are seeing shifting trends in fentanyl use.

As recently as last year, more than half of the people who sought help at TASC for heroin abuse turned out to be unknowingly using fentanyl, Terrell said in a previous interview. Now, a growing number of people are knowingly using fentanyl to the point that TASC now sees “relatively little heroin use,” Terrell said.

TASC saw 499 unique patients in 2021 and had 389 active patients as of last week.

“Unlike even just a year ago, or two years ago, people now are seeking out fentanyl because they can use a smaller amount,” Terrell said. “It’s less expensive than heroin. The number of people knowingly and unknowingly using fentanyl, unfortunately, is naturally going to lead to more overdoses in our community.”

But it’s not just the prevalence of fentanyl that’s increasing, said Bartholomew County Coroner Clayton Nolting.

“The amount (of fentanyl) that is in our fatal overdoses is increasing as well,” Nolting said. “…When I look at overdoses, let’s say three years ago, it was (on average) eight nanograms (of fentanyl) per milliliter of blood. Now we’re seeing the average being upwards of 11 to 13.”

“The primary drug of abuse in Columbus is still methamphetamine,” Nolting added. “However, the primary fatal drug in drug overdoses is becoming fentanyl.”

The update from the local officials came as the federal government reported that U.S. drug overdose deaths reached another record high over the latest 12-month period on record.

On Wednesday, the CDC estimated that 104,288 Americans died of drug overdoses from October 2020 to September 2021 — including a record 2,666 people in Indiana.

Overdose deaths have been rising across the country for more than two decades and now surpass deaths from car crashes, guns and even flu and pneumonia, The Associated Press reported. The total is close to that for diabetes, the nation’s No. 7 cause of death.

By comparison, there were about 52,000 overdoses deaths in the United States during the 12-month period ending in September 2015, including around 1,200 deaths in Indiana.

A ‘tragedy’

For its part, the Alliance for Substance Abuse Progress, or ASAP, called the local increase in overdose deaths a “tragedy” and said that more work needs to be done to combat substance use disorder.

Launched in 2017, ASAP is a community-wide response to address substance use disorder, including the opioid crisis, in Bartholomew County. ASAP was formed through a partnership between the Columbus and Bartholomew County governments and Columbus Regional Health.

“It is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic continues to cause great harm to many communities, including those affected by substance use disorder, said ASAP Director of Operations Matthew Neville.

“Every overdose is a tragedy and every life lost leaves a hole in a family that can never be fully repaired,” Neville said. “Bartholomew County’s overdose numbers show the continued work that is required to combat substance use disorder in our community.”

But as the drug crisis continues to evolve, local officials look ahead with a sense of trepidation and uncertainty, wondering what is next.

“The people who make these drugs are pretty slick and pretty smart, and so I do worry about what’s the next fentanyl,” Terrell said.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic Ashley Brown, with Alliance for Substance Abuse Progress Bartholomew County, helps set up a display of shoes on the steps of Columbus City Hall before an International Overdose Awareness event in Columbus, Ind., Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic Shoes and electronic candles were on display on the steps of Columbus City Hall before an International Overdose Awareness event in Columbus, Ind., Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic Bartholomew County Coroner Clayton Nolting is shown during an interview at his office in Columbus, Ind., Wednesday, May 1, 2019.

Andy East | The Republic

Mike Wolanin | The Republic A view of the hallway leading to the entrance of the Alliance for Substance Abuse Progress Bartholomew County Hub in Columbus, Ind., Monday, June 15, 2020.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic A view of the hallway leading to the entrance of the Alliance for Substance Abuse Progress Bartholomew County Hub in Columbus, Ind., Monday, June 15, 2020.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic Dr. Kevin Terrell poses for a photo in his office at the Columbus Regional Health Treatment and Support Center in Columbus, Ind., Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Dr. Terrell is the medical director of the center.

Mike Wolanin | The Republic Dr. Kevin Terrell poses for a photo in his office at the Columbus Regional Health Treatment and Support Center in Columbus, Ind., Wednesday, June 9, 2021. Dr. Terrell is the medical director of the center.