Indianapolis Indians outfielder Chris Sharpe takes a turn at bat during a game on June 19, 2021.

Submitted photo

By Andy Bell-Baltaci

For The Republic

Under the bright lights of Victory Field, some players make less than many of their adult fans.

The Indianapolis Indians are the Triple-A farm club of the Pittsburgh Pirates, one level below Major League Baseball. The players on the field are in the top 1% of everyone who ever touched a baseball at the varsity high school level.

Fewer than one in 13 high school players will play in college, and fewer than one in 10 of those who play in college will ever be signed by a major league team, according to the NCAA.

But the MLB draft isn’t like the NBA or NFL drafts, where players go directly to the top level of the game. Players who get drafted have to go through the minor league system, and most minor league players won’t ever get the chance to sign a major league contract. For those top 0.8% of players who aren’t yet in a major league uniform, playing baseball doesn’t include fame, luxury cars or mansions. Instead, it has included second jobs, relying on teammates and family members for financial help — and deciding whether or not the dream they’ve been chasing for most of their lives is worth it.

Becoming a star

Indianapolis Indians pitcher Beau Sulser’s dream was sustained at the very end of his collegiate playing career. The pitcher grew up in a sports family — his father was a high school football player, and his older brother Cole picked baseball as his favorite sport early on.

Indianapolis Indians pitcher Beau Sulser, left with his brother, Baltimore Orioles pitcher Cole Sulser, during 2019 spring training in Sarasota, Florida.

Indianapolis Indians pitcher Beau Sulser, left with his brother, Baltimore Orioles pitcher Cole Sulser, during 2019 spring training in Sarasota, Florida.

Submitted photo

“Usually you follow the older brother, and he liked baseball more than any other sport,” Beau Sulser said. “My mom didn’t play sports. My dad played high school football, and nobody was into baseball, but my dad was very, very involved once we picked a sport and did everything in his power to make sure we got every opportunity to practice at the sport. Once we picked baseball, it was everything. I followed the footsteps of my older brother, and he liked baseball, so I liked baseball.”

Beau Sulser followed those footsteps across the country from their home in southern California to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, playing his freshman year the same season Cole Sulser was a fifth-year senior recovered from Tommy John surgery.

“I’ve always known (playing professionally) was a possibility,” Beau said. “We were told by our dad, ‘If you’re going to do something, it’s worth doing well.’ We had some people from my hometown in the minor leagues but they never made it (to the majors). But in high school, I knew I would at least get the opportunity to play college baseball and get an education, which was already an exciting time. If all went well, I’d have the opportunity to play at the professional level.”

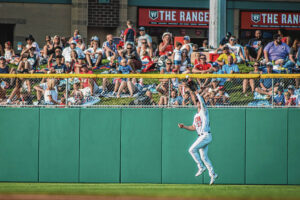

Indianapolis Indians outfielder Chris Sharpe catches a fly ball during a game on July 4, 2021.

Indianapolis Indians outfielder Chris Sharpe catches a fly ball during a game on July 4, 2021.

Submitted photo

Another Indy Indian, outfielder Chris Sharpe, is entering his fifth minor league season. Sharpe was born and raised in Massachusetts, where watching the 2004 Boston Red Sox win a title for the first time in 86 years inspired Sharpe to consider baseball as a possible career, he said.

“Pedro Martinez, David Ortiz and Trot Nixon made baseball baseball for me and made me want to pursue it,” Sharpe said. “It made my love for baseball solidified.”

After committing to Salem State University, a Division III school, out of high school, it didn’t look like Sharpe would be in any position to get drafted. But he took a gap year and went to a prep school, performing well enough to suit up for UMass-Lowell, a Division I school.

“I had a horrible freshman year. It was the first time I struggled in my life, baseball-wise,” Sharpe said. “Sophomore year I jumped off the map.”

During his sophomore year, Sharpe hit .338 with seven home runs and 25 runs batted in, and in 2017, became the 21st player in the school’s history to be drafted by a major league team.

Indians third baseman Hunter Owen grew up part of a baseball family in Evansville, with his father a former player for the Purple Aces and his brother a baseball player at Murray State. Owen himself started playing the game at 4 or 5 years old, he said.

“From the time I started playing baseball, it’s been my one true love,” Owen said. “It’s something I worked for my entire life. I really love all aspects of it. I love that it’s a team game and very individualized as well. I think there’s no better feeling than stepping into the box against a pitcher and being successful at the plate.”

Owen, who played at the University of Southern Indiana, said he consistently improved through college, and the support of his family helped him believe in himself.

“I think my family and support system helped throughout my whole life. With them behind me, we pushed each other to be the best we can. With help from my older brother and dad, I spoke it into existence,” he said.

“There was definitely some doubt. It’s a crazy game and early on in my college career, as a redshirt freshman, I got 15 at-bats. With my dad and brother behind me, I kept pushing forward, getting better and stronger. By the end, I got to be a pretty good ballplayer.”

Making sacrifices

Just like his brother, Beau Sulser was in his final year of college when he got drafted. While some of the top players in each draft class get multimillion-dollar bonuses when they get picked, players drafted in the later rounds, especially those who don’t have the option to go back to school to continue playing, get relatively measly sums.

For Sulser, who got picked in the 10th round, the bonus was $5,000, and with the cost of housing and student loans, that money dissipated. In the minor leagues, he has been taking home $2,000 a month — and during the winter, he didn’t get paid at all unless he got a second job, meaning his take-home baseball salary was about $12,000 a year.

“Training costs a lot of money for minor leaguers not getting paid,” Sulser said. “I’ve had offseason jobs. I’ve sold cars, and then my brother and I started some businesses that have done well and allowed me to work for myself.

“To show up to spring training every year ready to go, you have to train the whole offseason, not only for free but losing money because you have to pay other people (for workouts). It’s not necessarily the best setup. If you’re getting training and physical therapy work, you’re spending anywhere from $500 to $1,000 in training just in professional gym memberships and physical therapy work.”

This season, Major League Baseball will pay for minor league players’ living expenses, but when Sulser made his Indians debut last year, that wasn’t the case.

“In Indy, housing is $1,000 a month minimum, and when you’re taking home $2,000, you’re losing half your money right away finding a place to live,” Sulser said. “Then, you have food and activities and still have student loans and a car payment. Other bills start to add up.”

Sharpe, drafted in 2017’s 14th round, picked up a decent bonus with the help of an agent, more than what other players in his round were taking home.

“I had a few chances to go later in the first 10 rounds, but I turned those down with the help of an agent. I was playing in the Cape Cod League at the time and I heard my name over the radio we had that I got drafted. Me and the agent worked things out. (The bonus) was $256,000,” he said.

“I was just itching to play, any opportunity to play pro ball. I would take anything, and my agent really slowed me down and said, ‘There’s some money to be made here.’ We can do this the right way or I can handle it myself. If not for him, I may have gotten a lot less money than I should have.”

Sharpe needed that bonus. As a player on the now-defunct West Virginia Black Bears Single-A team in 2017 and 2018, he made $600 every two weeks. And even when he was called up to Indianapolis, the wages never outpaced the cost of living, with him taking home the same $1,000 every two weeks as Sulser.

“If you look around at all the other minor league sports, in the NHL and NBA, players are getting paid enough where they don’t have to worry about getting another job or having an apartment in the offseason if they don’t get a decent signing bonus,” Sharpe said.

Some players have to limit when and where they can eat due to their low salaries, or have to rely on teammates who have benefited from a major league salary at one point to pick up the bill, Sulser said.

“Guys would pick up the bill without even asking. One time I was eating, a bill was paid for by I don’t know which one of my teammates. They pick up the bill and players help other players out,” Sulser said. “You have to be aware and can’t do whatever you want. You have to know how much you’re spending when going out, how much you’re spending at dinner, or for significant others to visit. How often can they visit? Because flights are expensive, and with how expensive a hotel is on the road, we have to share a room — and if we want our own room, we have to pay for our own room.”

Owen, drafted in the 25th round in 2016, received a $25,000 bonus but said he could’ve been drafted earlier with better representation.

“If I could go back, I would seek a lot better representation,” he said. “I think I asked for too much in the early stages of the draft. I was a redshirt junior, treated as a senior, from Indiana State and didn’t know if a lot of scouts would have eyes on me. I think I was drafted very fairly and I appreciated getting drafted by the Pirates. It made me have a chip on my shoulder that allowed me to keep working.”

While in the minor leagues, Owen made the same salary that some of his teammates, such as Sulser and Sharpe, made: $600 every two weeks in Single-A. While family financial support helped Owen stave off poverty, people he knew weren’t so lucky.

“I saw people, who were very good ballplayers, forced into retirement because they couldn’t afford to play minor league baseball,” Owen said. “One guy was a hell of a first baseman and hit 15 or 16 home runs in high A. He had to retire the next year because he was getting married and his life was moving on. It’s a huge bummer to see, especially with a guy like that with a lot of talent.”

Small steps forward

The Major League Baseball Players Association, the union for MLB players, reached a deal last month to end a lockout instituted by MLB owners.

But the deal only assists players who are among the chosen few to step onto the field in a major league game. Career minor league players are left without a union, the ability to strike or negotiate, or the invitation to sit at the table when negotiations are conducted. While the minimum salary for Indianapolis Indians players increased from $1,000 to $1,400 every two weeks, in order for an Indians player to make a one-year minimum annual salary of a major league player, they would have to spend about 42 years playing for Indianapolis.

Only minor league players who donned a major league uniform get the benefits of a union. Such is the case with Owen, who went to the plate just four times in a Pittsburgh Pirates uniform last season as a 2021 call-up after Gregory Polanco violated COVID-19 protocols. As soon as Polanco rejoined the Pirates, Owen — who hit 20 home runs and drove in 53 runs for the Indians last season — went back down to Triple A.

Despite his short time with the team, Owen’s health insurance benefits improved, as did his salary. After his MLB appearance, he saw his minor league salary increase to $4,000 every two weeks, almost three times the current minimum for a Triple-A player.

Beau Sulser’s brother, Cole Sulser, also saw his dream of making a major league roster come to fruition. He’s now a pitcher with the Baltimore Orioles, making his debut at 29 years old for the Tampa Bay Rays in 2019 after six seasons in minor league baseball.

“I can’t put into words how lucky I am to see my older brother, who didn’t make his debut until 29 after two elbow surgeries and how much sacrifice he had to make that happen,” Beau said. “It’s hard. When you get drafted, around 5% of players make it to the big leagues. Getting drafted is technically the easy part. The grind of the minor leagues is really not as glamorous.

“People believe when you play professional baseball, you have a glamorous lifestyle, but it’s a lot of sharing rooms with other guys, a lot of saving money and eating super cheap, Top Ramen when you can. It’s having to be smart with money, and if you have a signing bonus, making it last as long as possible. It’s a lot of sacrifice.”

Sulser, Owen and Sharpe want to make sure they, and future minor league players, don’t have to face the same struggles going forward.

Players should get paid year-round, instead of having to rely on an offseason job to make money during the winter, Sulser said.

“I would love to get paid year-round. To perform in the top 1% in the world is a full-time job,” he said. “A lot of people think you just play the game at 7 p.m. During the season, you get there at 1 p.m. for a 7 p.m. game and then in the offseason, it’s a full-time job training with conditioning and lifting weights, throwing, hitting, all your training and paying for those opportunities. Whether it’s a gym membership, or a facility to hit and throw in if you’re in a snowy area, training costs a lot of money for minor leaguers not getting paid.”

Players need to get a significant pay increase if there is any hope of making a living in American baseball outside the major leagues, Sharpe said.

“In baseball, there’s no way we can live off what we make in salary. (MLB is) paying for living arrangements this year, but it’s only the start of where we should be. What we do, what we sacrifice to be here, everyone would kill to be playing baseball. It’s unacceptable to make what we get paid.”

In order for minor league players to attain better working conditions, they should be represented by a union, Owen said.

“I think they definitely should have a union,” Owen said. “I think it’s kind of crazy that minor leaguers have to perform and basically they have to train all year long and have this job. It’s a full-time job, and guys expect them to live well under the welfare line and it’s kind of criminal in my mind. I think a minor league union would really help.

“I think it’s a shame that a lot of guys are forced into retirement that can really play.”