Estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau show that Bartholomew County’s population grew at a faster rate last year than the nation as a whole, which some local officials say may bode well for the community as it continues to rebound from the pandemic.

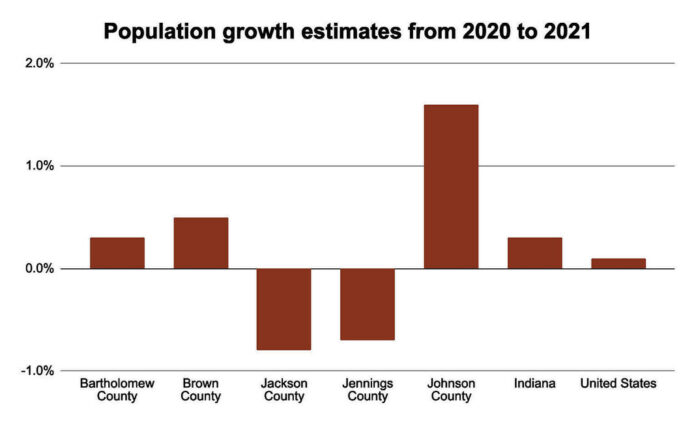

The latest estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau suggest that Bartholomew County’s population grew 0.3% from July 2020 to July 2021, adding 267 people and raising the estimated population to 82,475.

By comparison, Bartholomew County’s population grew by an average of 0.7% each year from 2010 to 2020, or roughly 512 people, according to previous Census Bureau estimates. However, the 2020 Census results for the county came in at 1,571 less than the 2019 population estimate of 83,779.

Bartholomew County, for its part, matched Indiana’s 0.3% estimated growth rate and exceeded the national rate, with the Census Bureau reporting that U.S. population growth dipped to its lowest rate since the nation’s founding during the first year of the pandemic as the coronavirus curtailed immigration, delayed pregnancies and killed hundreds of thousands of U.S. residents, The Associated Press reported.

From July 2020 to July 2021, the United States grew by only 0.1%, with an additional 392,665 added to the U.S. population, bringing the nation’s count to 331.8 million people.

Local officials characterized the estimated uptick in Bartholomew County’s population as “good news,” but were quick to caution that the Census Bureau figures are estimates that have margins of error and could be revised later. Additionally, one year of data likely isn’t enough to draw firm conclusions or make projections, they said.

The population estimates are derived from calculating the number of births, deaths and migration in the U.S., according to wire reports.

“In general, I think that population growth is beneficial, and it’s important,” said Columbus Mayor Jim Lienhoop. “…You can grow, or you can decay. For me, it’s always been important to grow, whether that’s personally or professionally, or as a community. So, I welcome the fact that we continue to grow. I know that for the communities to grow, that that brings some challenges. But I also believe that the challenges associated with a reduction in population would be more difficult.”

Pandemic-related effects

The estimates, however, shed some light on the extent to which the U.S. population shifted during the pandemic. The U.S. has been experiencing slow population growth for years, but the pandemic exacerbated that trend, according to wire reports. This past year was the first time since 1937 that the nation’s population grew by less than 1 million people.

The pandemic intensified population trends of migration to the South and West, as well as a slowdown in growth in the biggest cities in the U.S.

Earlier this month, the Census Bureau reported that there was a stark increase in deaths outpacing births across the country from mid-2020 to mid-2021, according to wire reports. Almost three-quarters of U.S. counties experienced a natural decrease from deaths exceeding births, up from 55.5% in 2020 and 45.5% in 2019. The trend was fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as fewer births and an aging population.

A total of 75% of Indiana’s counties saw a natural decrease in population last year, up from 50% in 2020 and 33% in 2019, according to the Census Bureau.

Experts say once there’s a handle on the pandemic, the U.S. may eventually see a decrease in deaths, but population growth likely won’t bounce back to what it has been in years past because of fewer births, according to wire reports.

Bartholomew County may have experienced a “drain” to some extent during parts of the pandemic, with thousands of workers not being required to be in the office, said Stephen Mohler, IUPUC assistant professor of management, who is a speaker on the university’s Indiana Business Outlook Panel.

Some workers moved out of town, and it’s currently unclear to what extent they are coming back now that Cummins Inc. and other local employers are starting to return to the office.

Most Cummins office workers are expected to have “hybrid” work arrangements — meaning that they will work part of the time in the office and part of the time at home or elsewhere — though some positions were expected to remain fully remote, company officials said in earlier interviews.

On Friday, the company had job openings for a remote senior developer and software engineers, according to job postings on its website. At least three vacancies posted over the past couple months and listed for Columbus were described as “100% remote,” with up to 10% travel or “periodic travel” post-pandemic.

“I’ll be curious to see the impact and the influence of (workers returning to the office), because I think a lot of people were glad to work from home, and now we’ll see how they are when they go back to the office,” Mohler said.

“The brain drain in Columbus, or any other Indiana location, if you look back, that’s been going on for a while,” Mohler said later in the interview.

Neighboring counties

Not every county in the Columbus area saw population growth last year, according to the Census Bureau estimates.

Jennings County lost 204 residents last year, with its population sliding 0.7% to 27,409 — the county’s lowest headcount since 1997, according to Census Bureau estimates.

Previous Census Bureau estimates suggest that Jennings County’s population has ticked down in eight of the previous 12 years on record, losing 4% of its population since peaking in 2009.

Jackson County saw an estimated 0.8% drop in population, sliding down to 46,067, though that is still higher than the Census Bureau’s 2019 population estimates for the county.

Many of the highest one-year growth rates were seen in counties bordering Indianapolis, with Boone, Hamilton, Hancock and Hendricks counties each recording an estimated growth of 2.4% to 3.2%.

Johnson County saw a 1.6% increase, while Brown County recorded a 0.5% increase, the estimates show.

But the estimated declines in two neighboring counties have raised some concerns because — at least pre-pandemic — thousands of people living in those two counties were commuting into Bartholomew County to work.

Lienhoop said a decline in the population of neighboring counties would be a concern “because sooner or later, their issues are our issues.”

“I do believe that the health of our community depends in large part upon the health of the neighboring communities,” Lienhoop said. “I would continue to think that they’re great places to live, and perhaps part of what you’re seeing is pandemic-related issues, and it just take some time to sort out.”

In 2019, 4,571 residents of Jackson and Jennings counties commuted into Bartholomew County to work — accounting for roughly 10% of Bartholomew County’s workforce, according to the Indiana Department of Workforce Development and the U.S. Census Bureau, which drew its data from tax returns.

Before the pandemic, a total of about 13,000 people were commuting into Bartholomew County for jobs “because we don’t have enough people,” Mohler said.

“That’s why that (decline) is concerning,” Mohler said. “…We depend on them for employees.”

Jason Hester, president of the Greater Columbus (Indiana) Economic Development Corp., said his office is focused on spurring regional economic growth but cautioned that one-year population estimates are not necessarily indicative of a trend.

“I think it will be important just to watch the trend over time,” Hester said. “So a one-year blip, I think, for us is nothing to get too excited about, and for Jackson County or our neighbors to the south, nothing to get too worried about.”

“Positive population growth is a good thing, but I wouldn’t put too much weight on a one-year change, partly because that is an estimate,” Hester added.

Local officials say they remain hopeful that Bartholomew County and the surrounding area will continue to grow in the future, though it might take time to sort out what kinds of longer-term trends emerge in the wake of the pandemic.

“As far as for us locally, I think it’s maybe too soon to really have a sense of what the pandemic may mean for our population,” Hester said.