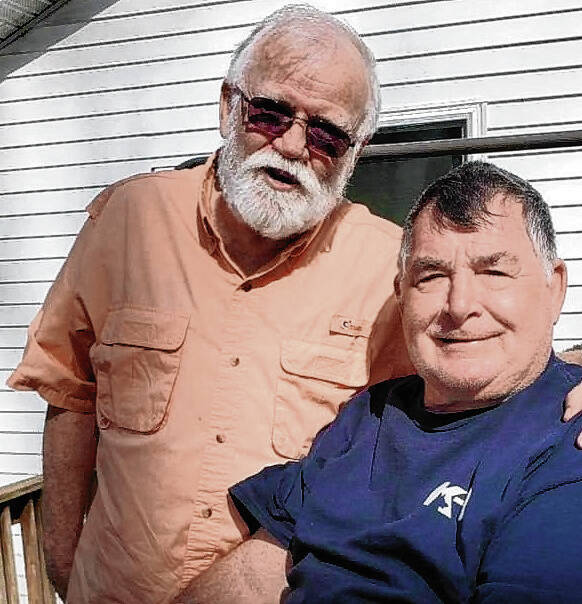

Ron Dougherty, left, now of North Vernon, socialized last year with fellow veteran and Columbus native Revis Underwood, who retired after serving 30 years in the US Air Force.

Photo provided

NORTH VERNON – As a retired dean at IUPUC looks back at his service in Vietnam, the memories of Ronald Dougherty, 71, remain all too vivid.

A 1969 graduate of Columbus High School, Dougherty recalled working for the Lindsay Company, a men’s clothing store once located in downtown Columbus, for nearly a year. His mother was just a few blocks away working at the former Lib’s Nook restaurant.

In early 1970, Dougherty received his notice from the U.S. Selective Service System. In April, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic and advanced technical training.

After a brief leave, the young Columbus man was sent to Vietnam as the member of a cavalry-mechanized group attached to the Americal Division stationed at the Chu Lai Combat Base, about 37 miles southeast of Da Nang.

With a specialty in being reconnaissance scouts, Dougherty’s unit often patrolled in an armored personnel carrier between their home base and Da Nang.

His unit found itself involved in 1971 when US President Richard Nixon approved a plan to invade the country of Laos in an effort to close off the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Historically, the invasion is considered a failure because Americans were not allowed to join South Vietnamese forces on the ground. Such an act was forbidden by an act of Congress, he said.

“While we didn’t talk about the politics involved, most of us were thinking that if we’re going to be in the war, they need to let us fight a war,” Dougherty said. “But they didn’t.”

His unit usually consisted of five tracked armored personnel carriers and at least one M551 Sheridan tank. While those military vehicles don’t let you sneak up on anyone, Dougherty said they are effective in finding US personnel and keeping enemy forces at a distance.

But then came Dec. 7, 1970. Dougherty and his squad were in a night camp when a member of his unit — SP4 Joe Crenshaw, 21, of Mobile, Alabama — stepped on a land mine. Two others right behind him – Thomas Rafferty of Michigan and Carmine Macedonia of Pennsylvania – died with Crenshaw in the explosion, Dougherty said.

“I was about 30 feet away when the landmine went off,” he said. “One minute I was talking to them. I had just turned away when ‘boom’!”

Before his tour of duty ended, Dougherty would see three more friends lose their lives in combat.

But perhaps the most emotional event the Columbus native experienced came in January 1971, while he was in the field. To his surprise, a helicopter assigned to a prominent Colonel picked him up and flew him to a chapel.

It was there that Dougherty received the tragic news that his mother was found dead in her Cambridge Square apartment after not showing up to work on Jan. 19, 1971. Her husband, D. Owen Dougherty, had died 10 years earlier.

As he was flown back to Indiana after being given a 30-day leave, the experience felt surreal to Dougherty – especially the fact that he was in southeast Asia one day and back home in Indiana the next, he said. Making him feel ever stranger was that he was alone in the passenger area during most of the flight.

“As much as the death of my friends defined my trip to Vietnam, my mother’s death had a bigger role,” he recalled. “She was only 59. When I left for Southeast Asia, I never expected it would be the last time I would ever see her.”

When Goldie Dougherty died, she left behind her mother, seven other children, six siblings, 15 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Her unexpected passing left much of the family in turmoil.

So much was happening that Dougherty says he can’t remember feeling traditional grief for the loss of his mother.

Instead, he felt guilt.

“I kept wondering what I could have done to save my mother if I were here,” the retired educator said. “If I were at home, would it have made a difference?”

Although his cognitive mind tells him no, his heart kept told him something else, Dougherty said.

For some time, the Columbus soldier tried to shut out all the pain he felt over losing his mother, as well as six brothers-in-arms in Vietnam.

“But I found that if you really want to get close to someone, you have to let them in again,” Dougherty said.

Since he has a friend residing near Mobile, he’s made annual trips to visit Joe Crenshaw’s grave. While unit reunions are held about every two years, Dougherty has found the most comfort being with a good friend and former Army buddy with whom he regularly shares heart-to-heart talks.

The veteran says he finds it comforting to visit Crenshaw’s grave, or frequently visit the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., similar monuments in Pensacola, Florida and Fort Wayne, as well as a touring wall that came to Columbus in July 2016.

When asked whether he experiences survivor’s guilt, Dougherty didn’t hesitate to say yes. But he also points out that survivor’s guilt isn’t exclusive to veterans.

“I know people who have been in a car crash where they survived and somebody else didn’t,” Dougherty said. “If you are human at all, you have to wonder: why not me?”

When Dougherty has posed that question to others, the most common reply has been that God has a different plan for him. He spent his last four months in Vietnam as a chaplain’s assistant before being discharged in December 1971.

Upon returning home, Dougherty returned to men’s clothing retail sales. But in January, 1975, he used his GI bill to study at IUPUC. After earning his business degree with a specialty in marketing, Dougherty began doing electrical work, as well as working in retailing for three more years.

But after being hired as a part-time instructor, Dougherty was eventually promoted to chairman of the school’s small-business management program.

With the Memorial Day weekend upon us, the now-retired educator and administrator is not oblivious to the politics and turmoil that divide Americans. In response, Dougherty makes one heartfelt plea to his fellow Hoosiers.

“You can hate the war,” Dougherty said. “But please respect those in uniform who are fighting it.”