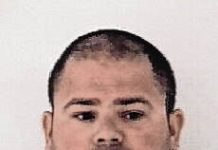

A Columbus man police arrested after he exposed himself outside of a Whiteland elementary school was at one time on the state’s sex offender registry, but had since been removed.

James P. Snodgrass, 62, was required to register as a sex offender after he was convicted of incest in 1996, but he is no longer on the registry.

The reason comes down to when the crime Snodgrass was convicted of was originally committed, and what the law was at the time, according to the Indiana Department of Correction.

According to court records, a relative of Snodgrass told police in 1994 that he had been molesting her for years. Based on the law, that would be the date that would be used to determine what rules Snodgrass would have to follow as a sex offender, said Brent Myers, Indiana Department of Correction director of registration and victim services.

Indiana first started a sex offender registry in 1994, and the laws have changed significantly since then, Myers said.

The registry is public, allowing residents to look up where offenders live or work near them. Sex offenders are not allowed to live within 1,000 feet of a school, youth center or park, and if they move, they must notify the sheriff’s department and the registry is updated.

Exactly what applies to Snodgrass depends on multiple factors, including the offense he was convicted of and his prior record, Myers said.

In 1994, when the registry was started, offenders only had to be on the registry while serving his or her sentence, including time spent on probation or parole. Snodgrass was sentenced to 20 years in prison and served all of that time, except about four months, and was released in December 2015.

How long he was on the registry after that depends on any parole he was ordered to serve and whether he had any past convictions for sex offenses, Myers said. And while Snodgrass had past convictions of public indecency, those offenses do not require someone to be listed on the registry, Myers said.

Since then, the law on who is required to register, and for how long, has continued to change.

After 1994, the state required offenders to remain on the registry for 10 years after they finished probation or parole. Later, that was changed to require them to register as soon as they were released from prison, Myers said.

In 2001, the state required some offenders to register for a lifetime for specific offenses, including if the victim is younger than 12 or if force was used, he said.

But in addition to those sweeping law changes, smaller tweaks have been made as well, based on court cases challenging the law, he said.

One case successfully argued that offenders should not have to register if the registry was not in place at the time the crime was committed. Another successful case was argued that offenders should not be required to register for a lifetime if the crime was committed before July 2001, when the state started requiring lifetime registration for certain offenders, Myers said. Both required changes overall once those cases were decided, he said.

Those legal changes and court cases require the department of correction to review every single offender to determine whether they have to register and for how long, Myers said.

Annie Goeller is a staff writer for the Daily Journal of Johnson County, a sister publication of The Republic.