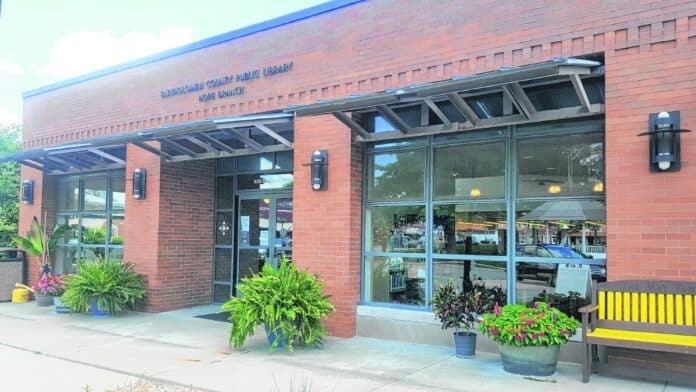

Bartholomew County Public Library officials closed their doors in mid-March to protect the staff and patrons against an invisible public health threat.

“We hope you understand that to interrupt our mission of providing access to people, ideas, information and experiences is something we only do because we feel we have no other choice,” library director Jason Hatton announced to patrons.

But Hatton and his 60 employees immediately began to steer patrons to tens of thousands of already available digital resources, and quickly created new virtual programming.

It was a good thing they had the courage and confidence to charge ahead into virtual programming, as the county library system’s initial anticipation of a three-week closure stretched out for three months.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

“Libraries are always changing our services and adapting to what the community needs,” said Hatton, who has been library director for five years and a library employee for 14 years.

But reinventing library services on the fly… “this is one of those watershed moments,” he said.

The library’s phased-in approach to reopening its physical locations began with curbside pickup

May 12 and porch delivery to home-bound clients May 18.

Buildings reopened June 15 with temporary hours to browse the library’s physical shelves.

Regular hours, still reduced from the pre-pandemic schedule, returned July 6 with limited seating spread out to encourage social distancing.

Through social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, as well as its website mybcpl.org, however, the library remained open around the clock for downloads and streaming services.

But the pandemic sped up an evolution of library services down a digital path that had already been fed into a GPS system of sorts, with directions displayed for the journey ahead.

Story hours that were held in the Columbus or Hope library buildings at scheduled times by Ms. Kate, Ms. Kelly and Ms. Lindsey, for example, were recorded so children could enjoy them virtually on a smart phone, tablet or computer — at times when it was convenient for them.

Prevented from returning to library buildings until June 10, story time hosts and other library employees worked from home — and the results were phenomenal, Hatton said.

A neighbor of his with a newborn and a 2-year-old is an example of one mom who benefited from the virtual story times with Ms. Kate. Since introduced, it has become a favorite part of their routine, he said.

Other examples of virtual programming are Friday Facebook Live concerts, arts and crafts, novelty programs such as Mr. Dave’s Garden, recipe discussion groups and library podcast episodes.

That’s on top of downloadable content such as eBooks and eAudiobooks, music and movies that long have been available.

But with patrons unable to step back into the physical library buildings until regular hours were reestablished this summer, eBook and eAudiobook checkouts soared.

Bartholomew County Public Library’s most-used eBook service, Overdrive, available since 2008, saw a 21.5 percent increase from February to May of this year. Hoopla, another eBook service, saw its numbers jump 74.5 percent during that span.

That compares to year-over-year downloadable eBook increases of 4 percent for teens, 11 percent for adults and 20 percent for juveniles from 2018 to 2019, prior to the pandemic’s discovery.

“This is a shift and it’s been good,” Hatton said of users’ increasing digital interest. “That’s how they want to consume.”

This year’s Community Summer Learning Challenge, “Imagine Your Story,” switched from physical books to virtual titles for its June 1 to July 31 run. Normally for children and conducted by the library alone, the summer reading program expanded to all ages and welcomed 12 community partners — most of them not-for-profit organizations.

Planning that normally takes a full year was condensed into two months, but you wouldn’t know it by participation levels. Through July 8, the virtual reading program drew 837 participants who read nearly 6,000 books and invested 574,785 minutes of reading time.

Reading took on the characteristics of a game and participants won badges and prizes, all the while enjoying a summer of reading while keeping their distance from others.

The library is surveying users to gauge ongoing interest in virtual programming. Although there’s no turning back at this juncture, the specific types of future digital services offered will be based on patron wishes, Hatton said.

About one-fifth of all library circulation last year was downloadable, meaning 80 percent of all materials borrowed were still ink on paper. Last year’s total circulation of 657,958 printed books was the highest since 2013, so don’t worry that printed books are about to go away.

During the pandemic, however, processing of books gets done differently. When books are returned, they are stored in the library’s lower level for a 72-hour quarantine before going back onto the shelves.

“We feel confident that the materials are safe at that point,” said Hatton, relying on guidelines from the U.S. Institute for Museum and Library Services.

With the number of in-library customers substantially off pre-pandemic levels, there is plenty of time for staff members to wipe down library tables, shelves and desks, Hatton said.

He is confident that more patrons will return to the buildings when they are comfortable doing so.

With 46,000 active users holding traditional library cards and another 4,500 to 5,000 with digital library cards offering immediate access, the library system is reaching a majority of Bartholomew County’s 84,000 residents — and the numbers keep climbing.

From 2018 to 2019, total circulation for physical and downloadable books was up 11 percent.

“People often forget how monumental the library services are,” Hatton said.

Since low-income areas of Bartholomew County are less apt to have internet access, the library’s Book Express program delivers free books into these neighborhoods and school lunch sites in an effort to reach all residents with services.

With a $4.1 million operating budget for this year, about two-thirds of that comes from property tax revenues — about $45 a year for the average household, or the cost of purchasing two books on their own — and the remaining one-third from income taxes.

Free-service libraries always experience increased activity during economic downtowns, so Hatton is bracing for higher demand for services until full employment returns.

With movie theaters and concert halls closed and bars and restaurants operating at reduced capacity, public libraries are positioned to entertain people while they wait for life to return to normal.

That’s an ending to a story we’re all anxious to read.

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”Bartholomew County Public Library” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

Locations: Main library at 536 Fifth St., Columbus; Hope branch at 635 Harrison St.; satellite operations at the Anderson Community Center, 421 McClure Road, and the Boys and Girls Club, 405 Hope Ave.

Phone: 812-379-1255 for Columbus library; 812-546-5310 for Hope branch.

Website: Visit mybcpl.org for hours, services and programming.

[sc:pullout-text-end]

Retired editor Tom Jekel writes a weekly column that appears each Sunday on The Republic’s Opinion page. Contact him by email through [email protected].