By Harry McCawley

Bartholomew County has had its share of witnesses to history — individuals who may not have made history themselves but were in the wings when it was made.

Jonathan Moore, the one for whom a portion of Indiana 46 west of Columbus is named, probably ranks as the earliest local witness. He served in the elite Life Guard assigned to protect and tend to the personal needs of Gen. George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

Apparently one of his duties related to making sure the general was clean shaven. Among the items passed down to his descendants were a razor and strop used to sharpen the blades which had been used by the general and given him to Moore.

Kyle Shipp talks to his Whiteland girls basketball team during a game in 2019. Shipp has been named girls basketball coach at Hauser.

The Republic file photo

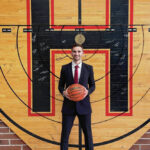

Trent Moorhead poses in front of the old center court at the entry to the Hauser gym Tuesday after being named the Jets’ new boys basketball coach.

Submitted photo

His connection to the county came about several years after the young nation won its independence when he moved here from Ohio, shortly after Bartholomew County was created in 1821. According to military pension records he had worked as a tailor while living in Ohio but by the time he moved here when he was 64, infirmities associated with old age incapacitated him. Ironically, he would live to be 99 years old and is buried in Sharon Cemetery.

Another well-known local witness was Barton Mitchell, who was a foot soldier for the Union during the Civil War. It was during a rest period in a march along the Maryland countryside that he was thrust into a pivotal moment in American history.

As he sat on the ground, the soldier noticed a package alongside the road. At first he couldn’t believe his luck as the package contained several cigars. It was when he took the cigars out to share with a fellow soldier that he noticed another infinitely more valuable item.

The package contained the battle plan drawn up for Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. It outlined in detail how his forces were to be deployed for the approaching encounter with Union forces at the small Maryland town of Antietam.

Mitchell took the plan to his superiors, who used it to fashion their own plans for the battle which Lee saw as a prelude to an invasion of the North.

What followed was one of the bloodiest campaigns of the Civil War, one the North would have lost had Mitchell not “discovered” Lee’s lost order. As it turned out, the costly campaign resulted in a draw but Lee was forced to withdraw.

Like Moore, Mitchell came to Bartholomew County late in life. He and his family settled in an area around Hartsville and he died in 1868, six years after making his historic discovery. He is buried in the Hartsville Baptist Cemetery.

It is only in recent days that another Bartholomew County witness to history has emerged — one who also served during the Civil War and was called upon in the days immediately following the war’s conclusion to perform a sad but important duty.

Jariah Dinkins was assigned to stand guard over the body of the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln as it lay in state at the White House.

Dinkin’s story relates much more to Bartholomew County than those of Jonathan Moore and Barton Mitchell.

Unlike the two latecomers, he was born and raised in Bartholomew County. His parents were Henry and Polly Price Dinkins and he lived most of his life, before and after the war, in Elizabethtown.

In 1861, shortly after the war began, he enlisted in the 19th Indiana Infantry and was assigned to Company H. According to the book, “Iron Men, Iron Will,” by Craig L. Dunn, the 19th fought in several bloody encounters and Jariah Dinkins was in the thick of them.

According to Dunn, the young Elizabethtown soldier was wounded twice. On one occasion he walked seven miles from the battlefield to an aid station where he was treated for his injuries.

He came to his moment in history in the days immediately after the war ended when he used a pass to travel into Washington. It was late in the evening on his way back to camp that he first heard the news of Lincoln’s assassination from a passing stranger.

His trip back to the camp was interrupted when he was stopped by sentries in the area. Ironically, he was not held under any kind of suspicion but was instead enlisted by an officer to perform an unusual and highly honored assignment — to guard the body of the president.

For the next night and two days, the Elizabethtown soldier stood over the body of Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

Years later he told of his feelings. “Lincoln was a great man. It is a pity he didn’t live to finish the great work he had started. His vision and patriotism and firmness in the right were an inspiration to all of us.” Ironically, he had voted a Republican ticket only once in his life. On that occasion in 1864 he voted for Lincoln as president.

After being discharged from the Army, Dinkins returned to Sandcreek Township where he farmed for most of the rest of his life. In his later years he became incapacitated and was forced to move to Indianapolis, where he could be cared for by his daughter. In 1937, six years after the move to Indianapolis, he died at his daughter’s home.

His remains were returned to Bartholomew County and he was buried in Newsom Cemetery in Sandcreek Township.

The roles of Jonathan Moore and Barton Mitchell in American history have been long recognized in Bartholomew County, but that of Jariah Dinkins has been understated at best.

There is only one mention of his role as Lincoln’s “guard” in the archives of The Republic, and that was only a passing sentence in the middle of his obituary in The Evening Republican of Dec. 14, 1937.

That it has now come to light is due to a conversation between Steve Coffman, local camp commander of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, and David Skinner, who has been custodian for the Newsom Cemetery for more than 20 years.

“We were having lunch and near the end David asked if I knew that a guard at the services for Abraham Lincoln was buried in Bartholomew County,” Steve said. “It was the first time I had heard the story and I confirmed it through a lot of research on the internet.”

Steve didn’t let the matter rest at that confirmation. This last Memorial Day, members of the local Sons of Union Veterans included in their annual services a ceremony at Newsom Cemetery.

I suspect it marked the start of a tradition.

Harry McCawley is the former associate editor of The Republic. He can be reached at [email protected].