When I was in college and dating Jenny (who is now my wife), there was a Friday night in which we were planning to hang out. As the minutes, and then the hours, began to pass, I became increasingly impatient and angry that she was taking so long, not answering my phone calls and ruining our Friday.

But after several hours of waiting with no response, there was finally a knock at my door. And as she walked in, I peppered her with a litany of questions.

Where have you been?

What have you been doing?

Why are you so late?

I am certain I wasn’t listening to anything she was saying. There wasn’t an answer that would satisfy my anger.

But then, instead of trying to answer my questions, she just handed me a card.

And it wasn’t just any card.

It was a card that she had meticulously and patiently and lovingly crafted for me over the three previous hours. It detailed, in overwhelming specificity, all the memorable moments we had shared together and how much she loved me.

I got silent.

Like stick-my-foot-in-my-mouth silent.

Despite my anger and bewilderment, and the fact that it would have been easier for her to simply withhold the card, or just break up with me because I didn’t deserve the card, she demonstrated her unwavering love by giving it to me anyway.

My anger turned to regret.

It was her kindness, not her justified retaliation, that made me see my ugliness. It was her kindness, despite how I violated our relationship, that changed my heart.

When one is confronted with an undeserved kindness, it can be transformative.

And that is what we find in one of the most misunderstood parables of the Bible, referred to as the rich man and Lazarus. Many have used this moral story as a definitive proof text for eternity in hell, but it is far from it.

In the parable are two characters: the rich man and Lazarus.

From the grave, the rich man is confronted with how he treated Lazarus, a poor beggar, during his life. Upon facing the truth of how poorly he treated him, he was filled with sorrow.

Even though this parable uses words like Hades, torment, and suffering, it is not talking about hell.

What if I told you that, in facing the truth of his life, the rich man is being tested and refined? And what if I told you that he is not being tormented by a wrathful God, but transformed and restored into a right relationship with God and others? What if I told you that what he is experiencing is not suffering, but rather the pain of regret and the consuming sorrow of facing this truth about his life?

That is what the biblical text actually suggests.

The rich man is experiencing odynáō, which is a Greek word that means consuming sorrow.

More importantly, the word básanos, which is translated as torture in this parable, actually means a touchstone. A touchstone is a black silicon tablet, like slate, that is used to test the purity of soft metals.

To me, this implies that there is a process one goes through to determine the quality of one’s life.

Absolutely fascinating.

This reminds me of Paul’s words to the Corinthians when he writes:

“Each one’s work will become manifest; for the Day will declare it, because it is revealed (or tested) by fire, and the fire will prove what kind of work each person’s is. If the work that someone has built endures, he will receive a reward; If anyone’s work should be burned away, he will suffer loss, yet he shall be saved, though so as by fire.”

Interestingly, this is exactly what we find in another parable called the “unmerciful servant.”

For context, Peter asked Jesus how many times a person ought to be forgiven. Jesus responds that we should not simply forgive seven times, but rather forgive “seventy times seven.” This is a direct reference to The Year of Jubilee within Judaism.

According to Jewish law, the Israelites were instructed to celebrate a Sabbath year at the beginning of every seventh year. This meant that every seventh year the land, animals and people were to be given a rest from work. It was a time for rejuvenation and replenishment.

After seven cycles of seven Sabbath years (49 years) the people would celebrate by proclaiming freedom throughout the land, returning land to their original owners and cancelling all debts. The poor would no longer be oppressed and slaves would be set free.

This was The Year of Jubilee.

It was a time of resetting and righting inequities and injustices.

So what about a cycle of 70 Jubilees times seven?

Theologian N.T. Wright writes, “That sounds like the Jubilee of Jubilees! So, though 490 years — nearly half a millennium — is indeed a long time, the point is this: when the time finally arrives, it will be the greatest ‘redemption’ of all. This will be the time of real, utter, and lasting freedom.”

In answering Peter’s question, Jesus is suggesting that we keep forgiving until all is restored, that we keep forgiving until all is made right, that we keep forgiving until all are free, that we keep forgiving until all are redeemed, and that we keep forgiving until every debt is paid.

That’s when Jesus tells the parable of the “unmerciful servant.”

It is a story about a king who forgives the debt of a servant who owes him 20 years worth of wages. But then, the same servant goes to a fellow servant who owes him significantly less money and demands that he repay it immediately.

But because his fellow servant could not repay it, he threw him in prison.

With the idea of the Jubilee of Jubilees hovering closely in the background, where do you think this parable is heading?

How do you expect the king to now treat his servant who was unmerciful to the other servant?

The way the story is typically translated and understood by Christians is that, like the King, God will torture people in hell who are unmerciful to others.

But shockingly, guess which word also shows up in this parable?

Básanos.

The king, in his settled, controlled anger (orgē), hands the servant over to the inquisitor, not to be tortured, but to face the truth of who he had become and to test the quality of his life until the debt is repaid.

And what we know is that the only debt that needs to be repaid to God … is love.

In the context of the Jubilee of Jubilees, in light of this “greatest redemption,” we know that God is a God of forgiving all debts in love, forgiving until all is restored in love, forgiving until all is made right in love, forgiving until all are made free in love, and forgiving until all are redeemed in love.

And that is the thing about facing the refining fire of God’s love, or facing the inquisitor, or being salted with fire, it reveals the truth of who we are and how we have treated others. But, it is not for the sake of retribution and punishment. It is for the sake of individual transformation and wholly restoring a person into a right relationship with God and with others.

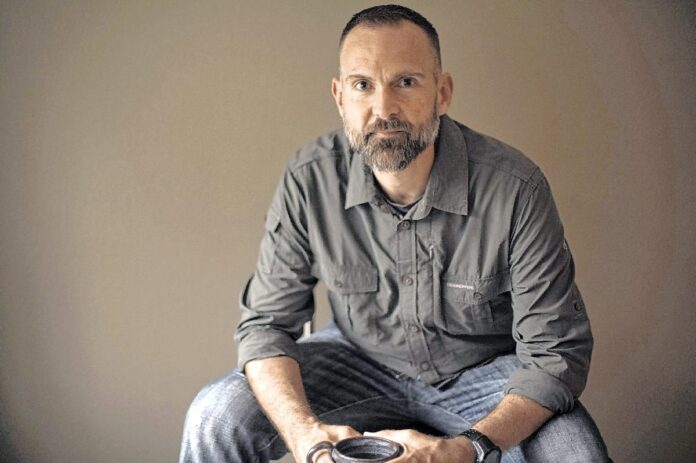

Brandon Andress of Columbus is a former local church leader, a Christian book author, a current iTunes podcast speaker and a contributor to the online Outside the Walls blog. His latest book is “Beauty in the Wreckage: Finding Peace in the Age of Outrage.” He can be reached at his website, brandonandress.com. All opinions expressed are those of the writer.