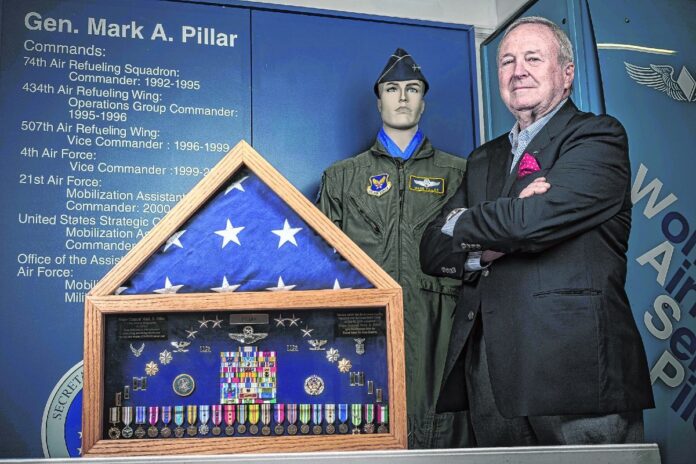

A 30-year airman who had recently risen to the rank of brigadier general was looking forward to the first day of his newest assignment.

Mark Pillar of Columbus was named mobilization assistant to the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Strategic Command, located at Offutt Air Force Base near Omaha, Nebraska.

On day one, Pillar would take part in the Pentagon’s annual training exercises where nuclear submarines would be dispersed, bombs would be loaded onto aircraft and the National Guard and Air Force Reserve would fuel up tanker airplanes during the Global Guardian war game.

Forty feet underground at Strategic Command, Pillar and other military officers began what was scheduled to be four days of training starting at 6:30 a.m. Central time.

It was Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2001.

‘That’s no accident. We’re under attack.’

At 7:50 a.m. local time, slightly more an hour into their exercises, participants were advised to put CNN on the large, eight-monitor viewing screen that stretched across the lower-level room.

Cameras showed smoke billowing from the World Trade Center’s north tower in New York City. It had been hit four minutes earlier by a commercial U.S. airliner.

People assumed it was an accident.

In due time, these military officers would learn that hijackers crashed American Airlines Flight 11 into the north tower, killing all 92 on board. Seventeen minutes later, the hijacked United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the commerce center’s south tower, killing all 65 aboard and scores more inside the building.

But in the moment, the group at Strategic Command was not even aware that commercial airplanes had been hijacked, despite flight crews having alerted staff on the ground, which in turn made the Federal Bureau of Investigation aware.

“As we saw the second one go in, the air was just sucked out of the room,” said Pillar, 52 at the time, a commercial pilot for Delta Airlines 12 days a month who committed 8 to 10 additional days to his duties with the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

“No one had ever weaponized an airplane like that — in that manner — since the kamikazes in World War II,” Pillar said.

Navy Admiral Richard Mies, the commander in chief of the United States Strategic Command who was also in charge of the training exercise, declared to the group: “That’s no accident. We’re under attack.”

In an instant, the day’s terrorism exercise had turned real-world.

“Our focus was to immediately mobilize to keep this from happening again,” Pillar said as Strategic Command and the 10 other combatant commands in the U.S. Department of Defense launched into a higher defense posture.

A deputy director of operations for the National Military Command Center coordinated communication efforts from the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., with about a dozen agencies — FBI, National Security Agency, Secret Service, Federal Aviation Administration among them — patched through on the call.

But the Pentagon itself was struck when a third hijacked airliner, American Airlines Flight 77, crashed into its western façade, killing 59 aboard and 125 military and civilian personnel inside the building. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who was inside the smoldering building, rushed to help others.

A fourth airliner controlled by hijackers, United Airlines Flight 93 with 40 aboard, then crashed into a field in rural Pennsylvania after passengers and the crew learned of the attacks in New York and Washington and attempted to retake the plane before it could reach its suicide-crash target, perhaps the White House or U.S. Capitol.

Working with the president

President George W. Bush was at a Sarasota, Florida, school that morning to read to second-graders.

Informed of the first two attacks, Bush returned to the skies and circled above Florida inside Air Force One for his personal safety, but was unable to talk with the outside world due to communication problems.

Ultimately, Bush flew to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana so the plane could refuel.

Meanwhile, Pillar and other military leaders in Nebraska immediately began looking into rumors or suspicions such as anthrax-carrying planes, poisoning of drinking water supplies and numerous bomb threats.

They also fielded questions on the conference call from the likes of Vice President Dick Cheney and National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice, secured in the White House basement, and Secretary of State Colin Powell, who was out of the country.

Since Strategic Command leaders were only given about 30 seconds to evaluate each of a battery of proposals ranging from closing New York bridges to evacuating the White House, the pressure was tremendous, Pillar said.

Actions that were approved included grounding thousands of planes flying across the United States and to be prepared to shoot down civilian airliners taken over by terrorists, Pillar said.

Other ideas such as shutting down the Global Positioning System (GPS) and halting financial transactions worldwide, related matters as banks rely on GPS timestamps in processing transactions, were rejected, he said.

“We knew not to do that,” Pillar said, rationalizing that such an action would have cost billions of dollars in financial losses.

Despite the stress that prevailed throughout the day, Pillar found a degree of comfort in his surroundings.

“You have all these great minds trying to figure out where the next attack is coming from and how to prevent it,” Pillar said of the civilians, military and elected officials working on a unified response.

Late that afternoon, Bush joined the strategists — with the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines all represented in Nebraska, where Pillar described the first-year president’s demeanor as steady and focused.

Bush sat at a console, linked by telephone to Defense Secretary Rumsfeld. Their conversation was piped into the large room, heard by dozens. After about seven minutes, however, Pillar said Bush was moved to a more secure area to participate in private video conference before re-boarding Air Force One and flying back to Washington.

At 8:30 p.m. Eastern time, Bush addressed the nation, condemning “evil, despicable acts of terrorism,” declaring that America and its allies would “stand together to win the war against terrorism.”

About an hour later, the Central Intelligence Agency’s Counterterrorism Center — briefing Bush and senior U.S. government officials — concluded that Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda were responsible for the attacks.

‘This was our Pearl Harbor’

After an intense 11 hours, Pillar was able to place a brief, reassuring telephone call to his wife Linda and teen daughter Lacey at home in Columbus at about 7 p.m. Sept. 11.

“I’m OK, don’t worry about me,” Pillar remembers telling his wife and daughter, while acknowledging being mentally exhausted. They were able to talk longer about three hours later.

On Thursday, following back-to-back 18-hour days, senior officers at Strategic Command gathered for dinner at the invitation of Admiral Mies, who arranged for a member of the base’s Air Force Band to sing and play his guitar.

One song especially resonated with the military crowd, Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” known for its familiar chorus, “I’m proud to be an American…,” Pillar said.

“We all stood up and sang it. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house,” the general said. “This was our Pearl Harbor. We watched it live as it was happening.”

Come Saturday, the Pillars were able to reunite at their west-side Columbus home, relieving some of the personal angst that had built up that week.

A different America emerged after 9/11, as a nation mourned the deaths of nearly 3,000 people.

Individuals faced greater security checks at airports, sporting events and concerts, but grew used to the idea.

In government, a new agency — the U.S. Department of Homeland Security — was created in 2002 to coordinate intelligence among government agencies, correcting a weakness exposed during 9/11.

And in neighborhoods across America, people demonstrated an outpouring of patriotism.

“Everyone flew American flags,” Pillar said, while all-volunteer forces protected the land and its democracy, in contrast to the Vietnam War era draft of his generation.

37 years of service

Pillar flew 90 Air Force reconnaissance missions in Southeast Asia from 1972 through 1973, “alone, unarmed and afraid” as he described it.

Three years after the Vietnam War ended, Pillar in 1978 transferred from full-time active duty to the Air Force Reserve, which allowed him to simultaneously begin a career as a civilian airline pilot.

Pillar was back in the military cockpit in 1990 for Operation Desert Storm and in 1991 for Operation Desert Shield in the Middle East, and a year later he defended the no-fly zone with NATO forces in Bosnia.

For his service, Pillar was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Meritorious Service Medal and Air Medal, among other honors.

Pillar’s last military duty assignment was working for the undersecretary of the Air Force at the Pentagon.

He retired as a two-star major general on June 13, 2008 —37 years to the day after he was commissioned a second lieutenant upon his graduation from the Reserve Officer Training Corp — when a flag in his honor flew over the U.S. Capitol building.

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”Inside today’s Republic” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

This story is part of The Republic’s annual SALUTE section, which publishes in conjunction with the Columbus Philharmonic Orchestra annual concert each spring.

Read more about retired two-star Maj. Gen. Mark Pillar, as well as the stories of other locals that have served, along with more information on Friday’s concert, inside today’s newspaper.

[sc:pullout-text-end]