When my wife, Ann, was a second grade pupil at Sellersburg Elementary School in the early 1950s, she was demoted from the “blue bird” to the “black bird” reading group.

Being a black bird was an almost unprecedented drop in classroom status for her — skipping stops at “red bird” and “yellow bird” and going directly to the bottom of the aviary classification system.

Blue birds were the kids who could read about anything placed in front of them — from Dostoevsky’s “War and Peace” to directions for repairing the school’s heating system.

Red birds were the kids who were able to read most of their textbooks with minimal prompting.

Yellow birds were the children who could make it slowly through graphic short stories featuring Dick, Jane and their dog Spot but had to pause before entering an unfamiliar restroom to sound out the word on the door.

Black birds had never heard of books that were not for coloring until they entered first grade and the scattered groups of letters on the pages meant nothing to them at all.

Ann’s drop from the elite list of blue birds — posted on the tack board next to the fire extinguisher just to the right of the American flag in front of the classroom — was not due to insufficient reading skills. She read well enough to one day be an honors student at Indiana University-Bloomington and hard-working enough to complete both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees over a span of four years.

Ann’s problems were a need to socialize and an overpowering desire to share her thoughts immediately with the teacher, other students, the janitor or the women in brown hairnets trying to ladle limp green beans onto her lunch plate.

In today’s world — where every student with learning challenges is provided with a defining label — Ann likely would have been declared to have attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Back then, the teacher just said she talked too much and sometimes got out of her seat without permission.

She spent much of first grade standing in the corner reading the instructions taped to the wall for evacuating the building in case of fire.

She entered second grade at the top of her reading group (probably from sounding out all those big words on the fire evacuation sheet). All of her grades were excellent, except for the “U” for unsatisfactory in “deportment” (school code for behavior) at the bottom of her report card.

In second grade, Ann was thrilled to find she had been designated a “blue bird” reader. But alas, glory was not long lived. She soon was back to her old stand-in-the-corner ways — talking to friends during class, answering the teacher’s questions without raising her hand and sharpening her pencils without permission.

Frustrated, the teacher decided drastic action was needed. The chosen punishment was to move Ann from her blue bird perch to the black bird reading group at the bottom of the bird cage.

Today, Ann still recalls that punishment bitterly — not because of any lingering humiliation over being demoted, but over what her demotion must have said to all the other black birds. If being a black bird was a punishment, these kids were being punished every day — not for talking or sharpening pencils without permission, but just for being behind the rest of the class in reading.

Decades later, Ann would be a high school English teacher at Franklin Community High School and would be known for her success in working with incoming black-bird freshmen who had not mastered the eighth grade ISTEP in English.

Odds are, she did a bit of black bird teaching in second grade as well, during her stay at the bottom of the reading group bird cage. At a minimum, everyone likely learned how to get out of the building in case of fire.

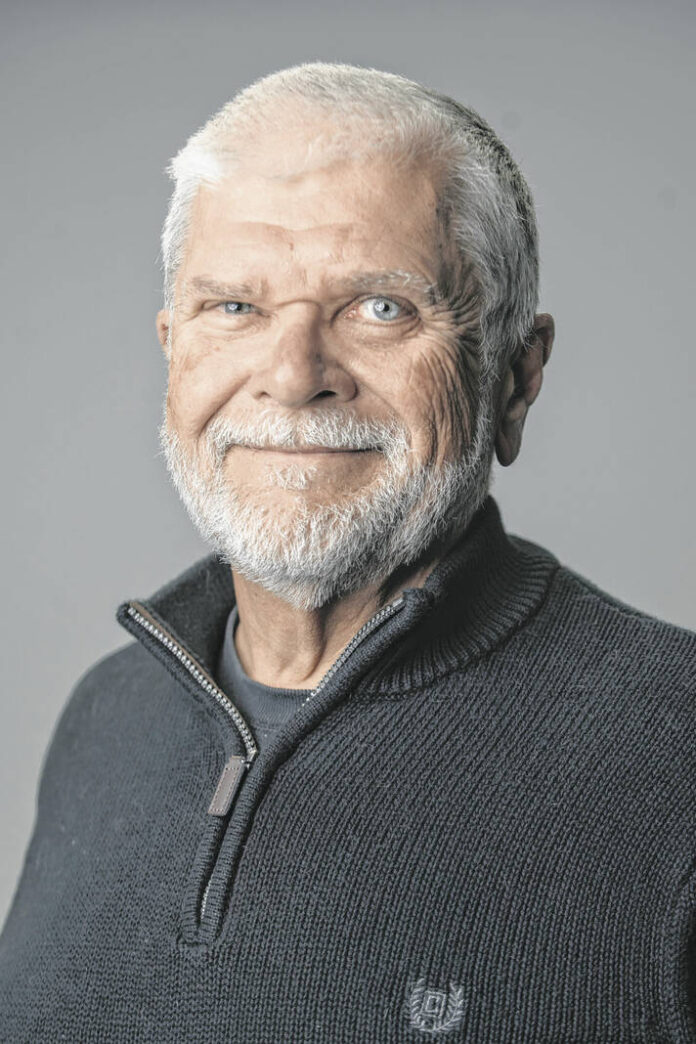

Bud Herron is a retired editor and newspaper publisher who lives in Columbus. He served as publisher of The Republic from 1998 to 2007. Contact him at [email protected].