It started out like a normal summer day for 8-year-old Daly Walker.

It was 1949, and the future Columbus Regional Hospital surgeon was playing Little League baseball in the town of Winchester, Indiana, unaware that his life was about to change.

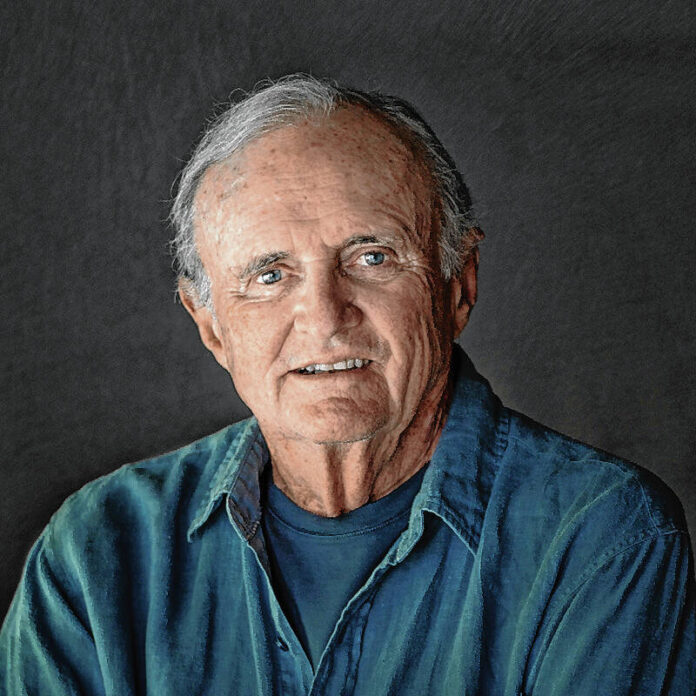

While on the baseball field, he suddenly started feeling sick. “I actually collapsed,” Walker, now 81, recalled 73 years later in an interview with The Republic. “I had a fever, and I was very weak. It was a very rapid onset. The coach carried me off the field. I was dizzy, and I was vomiting.”

What nobody knew at the time was that one of the most feared viruses in the world had invaded his body and was attacking his brain stem.

Walker said he was rushed to a local doctor who performed a spinal tap, a test in which a needle is inserted between two lumbar bones to remove a sample of fluid that can be used to diagnose medical conditions.

It didn’t take long for the doctor to figure out what was wrong: Walker had contracted polio, a disabling and life-threatening disease with no cure that struck fear in hearts of parents for decades during the first half of the 20th century.

While most infected people would have no visible symptoms, some children would develop an infection of the covering of the spinal cord or brain, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Others would develop paralysis in the arms or legs. Many polio survivors — including former President Franklin D. Roosevelt — were disabled for life.

Walker was taken to a hospital in nearby Muncie. He was soon joined by his older sister, who had also contracted polio, though she was not as sick as him and recovered. “We were in the same hospital room for a while,” he said.

‘Big epidemic in Indiana’

Walker, however, was just one of many children in Indiana who were stricken with the disease.

By the time he contracted the virus in late 1940s, polio outbreaks in the U.S. were increasing in frequency and size, disabling an average of more than 35,000 people, including more than 15,000 cases of paralysis, each year, according to the CDC.

Outbreaks periodically swept through cities and towns of all sizes. Walker said his father, who was a funeral director in the town of Winchester, buried 11 polio victims, including a young couple who left behind two children.

“There was a big epidemic in Indiana,” Walker said. “Riley Hospital was filled with children on iron lungs and paralyzed, as were other hospitals in the state.”

And Bartholomew County was no exception.

News coverage in The Republic at the time depicted periodic local outbreaks of polio and a state of fear hanging over the community.

Parents were scared to let their children go outside, particularly in the summer, when incidence of the disease was believed to peak. Public health officials would impose quarantines on homes and towns.

In 1946, health officials in Columbus closed all city playgrounds and pools, canceled Little League baseball games at Donner Park and barred anyone under the age of 18 from going to theaters after three cases of polio were confirmed in Bartholomew County.

At least four Bartholomew County residents — including three small children — died from polio in a two-month period in the fall of 1952.

By 1957, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis said there were 52 polio victims living in Bartholomew County, according to Columbus Regional Health.

‘It affected children more’

Motivated by his battle with polio, Walker became a physician, graduating from the Indiana University School of Medicine in 1966. Just a few years later, he moved to Columbus to take a job as a surgeon at CRH, where he worked for decades.

And now, decades after being hospitalized with polio, Walker received the news of the first case of the disease in the U.S. in nearly a decade with a heavy heart. Last month, an unvaccinated young adult in New York contracted the virus and developed paralysis, The Associated Press reported.

Just a few weeks later, New York state and federal officials confirmed that the virus that causes polio had been detected in New York City’s wastewater in another sign that the disease is quietly spreading among unvaccinated people, according to wire reports.

Recently, an unvaccinated young adult north of New York City contracted polio. On Friday, health officials in the nation’s largest city said they had found the virus in wastewater samples, suggesting it was spreading among the unvaccinated.

And an estimated 886 children ages 19 to 35 months in Bartholomew, Jackson and Jennings counties were behind on their polio shots as of this past March, state records show.

“It’s very sad to think this is coming back,” Walker said. “It can attack anybody, but they called it originally infantile paralysis because it affected children more than adults. It’s a problem for the pediatric population. I’d hate to see it resurrect itself again.”

Spared the worst

Walker said he was spared the worst consequences of polio. Because the virus attacks the brain stem — which controls breathing and swallowing — many children had to be put on ventilators called iron lungs to help them breath.

“Fortunately, my respiratory center was spared, so I did not go on an iron lung, although there were a couple nights when I had trouble breathing,” Walker said. “…My main problem was that my swallowing mechanism was paralyzed. So, I was unable to eat on my own. I was fed for many, many months by my mother (through a tube into his stomach.)”

In an interview 20 years ago with The Republic, Walker said his family set up a hospital bed for him in their dining room, and their house was put under quarantine. “They posted the notice on our front door,” Walker said in 2002. “People would cross the street so that they didn’t have to walk close to our house.”

Eventually, Walker was able to regain the ability to swallow, though somewhat impaired, and was able to “live a normal life.” But he still remembers the young couple who died of polio that his father buried some 70 years ago — and the two children who were orphaned.

Introduction of vaccines

But everything changed in 1955, when the first polio vaccine was introduced.

“When the polio virus vaccine was approved and was starting to be used, the whole community rejoiced,” Walker said, recalling how Winchester residents reacted to the news. “They were just ecstatic about that. They rang the church bells and cars drove around honking horns. When the announcement was made, my mother wept because she was so happy the other children and other families who wouldn’t have to experience what we had.”

By April 1955, almost 85% of parents of first and second graders in Bartholomew County had given permission for their children to get the vaccines, according to news coverage at the time. Later that month, more than 1,600 of those students had gotten their first dose.

The public’s reaction to the polio vaccine was different than it was for the COVID-19 vaccine, which many people in Bartholomew County still haven’t gotten. But that was a different era, Walker said.

“We had just come out of World War II and people, really as a nation, were united and working together to better our country, Walker said. “So, things like polio they attacked with a vengeance like they did World War II.”

Following the introduction of vaccines, the number of polio cases in the U.S. fell rapidly to less than 1,000 cases in 1962, less than 100 in the 1960s and fewer than 10 in the 1970s.

In 1979, the U.S. officially declared that polio had been eliminated in what has been viewed as one of the nation’s greatest public health victories, according to the CDC. Yet cases have cropped up occasionally since then, often among people who had traveled to other countries.

Walker, who became a writer after retiring and now spends his time between Florida and Vermont, developed post-polio syndrome a few years ago and his symptoms got worse. He underwent a procedure and was able to feel better, though “I just have to be a little careful.”

Walker is urging people to take the virus seriously and to get vaccinated.

“I’m just disheartened … to learn that it’s cropping up again and people aren’t getting vaccinated,” Walker said.

“It’s such a devastating illness, and the people that survived it with paralyzed legs and arms had a hard life after that,” he added later in the interview. “Although I was very ill, I was lucky that I didn’t have any paralysis on my extremities.”