Republic file photo The main entrance to the Cummins Engine Plant in Columbus, Ind., pictured Friday, Oct. 5, 2018.

Manufacturing in Bartholomew County is still rebounding from the hit it took more than two years ago when COVID-19 ripped through the community, throwing thousands of local residents out of work and briefly sending unemployment to its highest levels since the Great Depression.

Currently, officials say Bartholomew County’s economy still finds itself in “uncertain times” as global supply chain disruptions, labor shortages and decades-high inflation continue to hobble automotive manufacturing — the industry that experts say forms the “bedrock” of the local economy.

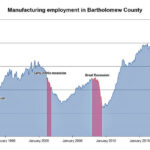

Last year, average annual employment in manufacturing in the county stood at 18,400, unchanged from 2020 — the year the pandemic struck — and the lowest figure in roughly a decade, according to data from the Indiana Department of Workforce Development.

As of this past July, there were 18,900 people in Bartholomew County who were employed in the manufacturing sector — 1,600 fewer workers than in July 2019 but up slightly from 18,700 in July 2020 and 18,400 in July 2021, state records show.

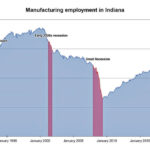

By comparison, statewide employment in manufacturing this past March had returned to where it was in March 2020, just before Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb issued stay-at-home orders and countless businesses across the state shut their doors to slow the spread of the virus.

Nationally, automotive production in June was 151,000 units, down 30% compared to where it was pre-pandemic, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. At one point during early days of the pandemic, U.S. automotive production plummeted to just 1,700 units in a single month, by far the lowest in records going back to 1993.

Bartholomew County, for its part, is particularly susceptible to the ebbs and flows in automotive manufacturing, as the local economy is more heavily focused on that particular area of the economy than most communities, said Steve Mohler, assistant professor of management at IUPUC and frequent panelist on IUPUC’s Business Outlook Panel.

In general, manufacturing accounted for 38% of non-farm employment in Bartholomew County in June, compared to 17% of employment statewide, state records show.

“Automotive manufacturing has slowed down,” Mohler said. “Therefore, Columbus has been impacted.”

One issue that has impacted automotive manufacturing is the ongoing global shortage of computer chips, which are used in a variety of automobile features and components, ranging from touch screens and cruise control to transmissions and partially automated drive safety features, The Associated Press reported.

The shortage, which can be traced to the eruption of the pandemic, has caused car makers — including Ford, General Motors and others — to slash factory hours, temporarily shutter production facilities and delay shipments of new vehicles, according to wire reports.

Cummins Inc., the largest employer in Bartholomew County, has been working to mitigate the impact of the shortage, with company officials acknowledging last year that there were some “sporadic impact on production.”

In July, former Cummins Chairman and CEO Tom Linebarger told President Joe Biden during a virtual meeting that Cummins, as well as the entire industry, is facing a “supply chain crisis,” including a global shortage of semiconductors.

“We are often buying chips from brokers and paying as much as 10 times the regular cost to get these chips just to make sure we can keep trucks on the road, driving inflation in our industry and challenges throughout our supply chain,” Linebarger said during the meeting.

Faurecia, a French automotive component manufacturer that operates locally, reported earlier this year that worldwide automotive production was impacted by “supply chain disruptions due to the war in Ukraine, by the continued shortage of semiconductors and the COVID-19 restrictions that have been implemented in China.”

Currently, it is hard to say when global supply chains constraints will ease, Mohler said.

“I don’t think everything is going to magically work itself out overnight,” Mohler said, referring to global supply chain disruptions. “I think there’s still a considerable period before we see things improve overall.”

In some ways, officials say they see some parallels between the current economic climate and Bartholomew County’s recovery from the Great Recession more than a decade ago, when the local economy saw a sharp decline in employment that stayed low for a couple years before it started climbing again.

However, one difference is that some 2,000 people in Bartholomew County left the workforce when the pandemic struck, while the county’s labor force stayed largely the same during the Great Recession, said Jason Hester, president of the Greater Columbus (Indiana) Economic Development Corp.

“We had a pandemic where we saw people leave the workforce,” Hester said. “We had a pandemic that removed some jobs from the market. So, what’s different this time is as the jobs rebounded, we didn’t immediately have everybody come back into the workforce. And the fact that we right now have exceptionally high inflation and recessionary concerns, it’s just another new twist.”

There is some good news for local employers, however. So far this year, about 1,000 people have re-entered the workforce, Hester said. And at the same time, there is still high demand in the automotive sector.

Hester, for his part, said “it feels like we’ve made the turn and that we are coming back out.”

“All in all, I’m not worried,” Hester said. “And we’re still exceptionally strong in manufacturing, which is the bedrock of our economy. Other things are pointing in the right direction, but obviously, there are a lot of really strong headwinds right now happening globally. So, again, time will tell.”

Jason Hester

Steve Mohler

Andy East | The Republic

Andy East | The Republic

Republic file photo A view of the Cummins midrange engine plant in Walesboro, Ind., Friday, March 20, 2020.

Photo submitted by Faurecia Faurecia opened its new digital manufacturing plant in Columbus, Ind. Oct. 4, 2016. The $64 million, 400,000-square foot facility features automated technology and a paperless environment.

Republic file photo The main entrance to the Cummins Engine Plant in Columbus, Ind., pictured Friday, Oct. 5, 2018.