IBJ photo/Eric Learned Virginia-based Electrify America operates an EV direct-current fast-charging station in a Meijer parking lot on East 96th Street. Indianapolis currently has only two fast-charging stations; the other is on South Emerson Avenue.

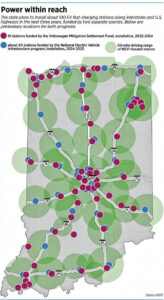

INDIANAPOLIS — Indiana officials are planning to install about 100 electric vehicle fast-charging stations throughout the state, mostly at interstate exits.

About 40 stations, including roughly a dozen in the Indianapolis area, will be partially funded through Indiana’s $100 million portion of the $1 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed last November. Part of that law created the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program, or NEVI, which aims to meet the Biden administration’s goal of placing 500,000 charging stations along U.S. interstates by 2030. Indiana officials hope to start installing the energy infrastructure for the NEVI-funded charging stations in 2024 and complete the project by 2025.

Coming even sooner to the state are 61 fast-charging stations planned for deployment beginning this year. Those stations will be funded primarily with $5.5 million of Indiana’s share of the Volkswagen Mitigation Settlement Fund that the carmaker paid for clean air violations. That program is being coordinated by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

Details about the NEVI-funded stations, like exact number and exact locations, are not yet public information. But one requirement is that some chargers must be placed in areas considered economically disadvantaged, encompassing both urban and rural areas.

Some groups say the state’s plan should also incorporate broader commitments to ethnically diverse communities and businesses. The Indiana Alliance for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion of Electric Vehicle Infrastructure and Economic Opportunities is calling on the U.S. Department of Transportation to reject Indiana’s plan.

While the NEVI funding is all but guaranteed, each state is required to submit a plan that describes how the money will be used.

To qualify for NEVI funds, charging stations must be installed along what are known as alternative fuel corridors— highways, interstates and other major thoroughfares — no more than 50 miles apart and within one mile of an interchange or intersection. In Indiana, that includes all interstates plus U.S. 31. INDOT also plans to nominate the U.S. 30 corridor across northern Indiana for inclusion.

The stations also must be direct-current chargers, called DC fast chargers; they are capable of charging 80% of an EV battery in less than 20 minutes for most cars.

Of the 325 publicly accessible EV charging stations in Indiana now, only five are NEVI-compliant.

The U.S. Joint Office of Energy and Transportation is expected to approve INDOT’s plan by Sept. 30. The state agency would then begin the process of contracting with partners to install, operate and maintain the charging stations.

Like many Midwestern states, Indiana has been slow to adopt EVs. The state ranks 25th in the number of registered electric vehicles, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Only 0.11% of Indiana’s vehicles are electric.

Combined with recent federal incentives, like the $7,500 tax credit to buy an electric car included in the Inflation Reduction Act, INDOT officials hope that installing strategically placed fast-charging stations across the state will nudge more Hoosiers to buy EVs.

“The way the NEVI program is structured really helps to overcome the obstacle to growing EV adoption,” said Scott Manning, deputy chief of staff at INDOT.

‘In a good position’

Industry experts believe a number of factors make the Crossroads of America well-suited for EV infrastructure.

Indiana has low elevation overall, with flat terrain that does not impede or create a challenging environment for transportation, INDOT’s plan notes. And while temperatures can sometimes be extreme, that’s typically only for short periods.

The state is also home to five automotive assembly plants. While none of them produces a purely electric vehicle yet, their parent companies — namely Subaru and Honda — are wading into the market.

Indiana also has more than 500 automotive parts suppliers and upward of 109,000 workers in motor vehicle manufacturing or parts manufacturing. These laborers are primarily trained to work on conventional internal combustion engine vehicles and their parts, but a number of programs and initiatives are already underway to prepare the state’s workforce for the transition to electric vehicles, a process expected to take decades.

“I think that it’s going to take a long time for the production of internal combustion engine vehicles—and maybe more importantly, hybrid vehicles—to go away completely,” said Paul Mitchell, president and CEO of Energy Systems Network. Mitchell is also a member of the Electric Vehicle Product Commission, a 10-member panel made up of legislative representatives and private-sector leaders to evaluate the EV product industry in Indiana.

Since 2008, Purdue University, Ivy Tech Community College and Vincennes University have received state funding to offer degrees in engineering geared toward battery systems, motor technology and modern computing that are required in today’s modern vehicles.

Auto manufacturer Stellantis NV and Samsung SDI are partnering to build a $2.5 billion electric vehicle battery plant in Kokomo, which is expected to create 1,400 jobs when it opens in 2024. And battery maker Ultium Cells LLC, a joint venture between General Motors Co. and LG Energy Solution, has filed a tax abatement application in St. Joseph County for an EV battery facility in New Carlisle that could bring more than $2 billion in investment and more than 1,000 jobs.

Rep. Mike Karickhoff, R-Kokomo, who authored the bill that created the EV Product Commission, said the panel is focused on receiving input from auto manufacturers, original equipment manufacturers and researchers.

“We are laser-focused on job retention, job creation and training our workforce,” Karickhoff said. “I think we’re in a good position.”

The commission plans to release its first annual report to the Indiana Economic Development Corp. on Sept. 30.

Coalition raises concerns

While the state’s NEVI plan has been well-received by industry experts, a coalition of Black-owned businesses, faith institutions, not-for-profits and civil rights groups in the Indianapolis area is calling on U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg to reject it because it doesn’t contain measures to ensure an equitable distribution of EV infrastructure.

Denise Abdul-Rahman, who heads the Indiana Alliance for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion of Electric Vehicle Infrastructure and Economic Opportunities, is also advocating for apprenticeship and training programs for Black and racially diverse people to have opportunities to participate in installing and managing the stations.

“The plight of our condition is so concerning that some of us are coming together around electric vehicles because we see the opportunity to make our communities more resilient to the impacts of climate change and air pollution,” Abdul-Rahman said.

The alliance is calling on INDOT to revise its plan to include commitments to post transparent metrics online that show progress of inclusion on the project and to place EV charging stations in Black and racially diverse communities, along with the supporting grid upgrades such stations need.

“There’s absolutely no commitment in the document of things they will actually execute,” said Pastor David Greene, president of Concerned Clergy of Indianapolis and a member of the alliance. “There has to be some intention that goes beyond a meeting or a conversation.”

Manning said INDOT conducted public outreach in disadvantaged communities, both urban and rural, and is looking to place almost half of its charging stations in racially diverse areas.

“We found that 20 of our 44 preliminary sites are in ethnically diverse areas,” he said. “So we have, I think, a very good baseline set of measurables with respect to equity.”

Manning said INDOT will continue to provide outreach for minority-owned businesses to participate in the plan.

The agency plans to begin installing the NEVI-funded stations in high-demand areas—as defined by traffic counts, EV adoption rates and utility readiness—as early as June 2024, with stations going live in the second quarter of 2025.

By the Indianapolis Business Journal

By the Indianapolis Business Journal