DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Iowa is directing nearly a million dollars in grant funding to expand summer meal sites for low-income kids.

It is an effort that advocates welcome, with worries that it won’t be enough to alleviate the barriers to access that were addressed by a separate federal program — providing roughly $29 million to Iowa’s low-income families — that the state rejected.

The state is allocating $900,000 to schools and nonprofit organizations that participate in certain federal programs designed to serve summer meals and snacks in counties where at least 50% of children are eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

The state’s funding would be used to either open new sites or to supplement existing sites’ expenses like local food purchases or community outreach.

Last summer, the two programs provided roughly 1.6 million meals and snacks to Iowa’s youth, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Still, only about 22,000 kids were served, compared with the more than 362,000 kids who received free or reduced lunches in school.

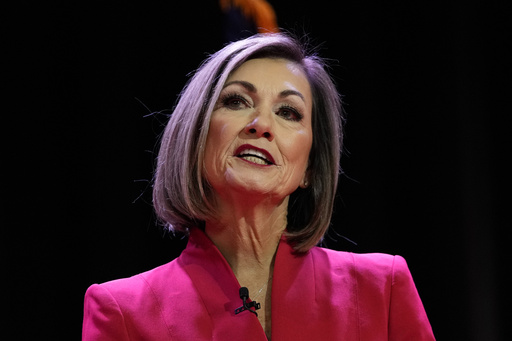

The announcement Wednesday follows Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds’ decision not to participate in a separate federal program that gives $40 per month for three months to each child in a low-income family to help with food costs while school is out.

More than 244,000 children were provided the pandemic summer EBT cards in 2023, according to the Iowa Department of Health and Human Services, amounting to over $29 million in federal funds.

Iowa is one of 14 states that turned down the federal money for a variety of philosophical and technical reasons.

States that participate in the federal program are required to cover half of the administrative costs, which would have cost an estimated $2.2 million in Iowa, the state said in its announcement last December.

“Federal COVID-era cash benefit programs are not sustainable and don’t provide long-term solutions for the issues impacting children and families. An EBT card does nothing to promote nutrition at a time when childhood obesity has become an epidemic,” Reynolds said at the time.

In a statement about the new funding, Reynolds said providing kids access to free, nutritious meals over the summer has “always been a priority” and that the expansion of “well-established programs” would “ensure Iowa’s youth have meals that are healthy and use local community farms and vendors when possible.”

Luke Elzinga, policy manager at the Des Moines Area Religious Council’s food pantry network, said the additional funds for summer meal sites are a good thing. But he worried that it won’t be enough to dramatically increase the number of kids helped or solve access issues that plague some communities.

“Summer EBT was not meant to replace summer meal sites,” he said. “It’s meant to complement them and fill those gaps in service and meet those barriers so families that can’t access a summer meal site will be able to have at least some benefits during the summer to help support their family’s food needs.”

The new grants will prioritize applications that would establish new sites in counties with two or less open sites last year. They will also heavily factor in the distance from the nearest site. The terms stipulate that applicants must operate for a minimum of four weeks when school is out.

Still, Elzinga worried that daily visits to a meal site throughout the summer would continue to be a challenge for some families, such as when kids have working parents, live more than a few miles from a site or live near a site that opens for a fraction of the whole summer break.

Elzinga said it was “ironic” that the new grants for expanded summer meal sites are being funded by state allocations from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, passed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s “pandemic-era money,” he said. “That is going to be used one time, this year, to expand summer meal sites. But what’s going to happen next year?”

Source: post