By Leo Morris

For The Republic

Because I am an old man, snow scares me. Sometimes, I think it is downright evil.

It weighs down the lines to my house, ready to snap them and plunge me into the cold and dark.

If I try to escape, I will find it piled on the porch, ready to grab my feet out from under me, or waiting on the walkway, enticing me to grab a shovel and fall over in a sweaty heart attack.

And if I make it to the car, I will start it with trepidation, knowing that every patch of white might have hidden depths to trap me in the middle of nowhere or a bottom layer of ice that will send me careening into oncoming traffic.

I can only wait it out, nervously hoping for a thaw. Last week’s snowfall, the late but still unwelcome first major storm of the season, meant 48 hours of anxious dread.

It was not always so.

In my youth, snow was a pure pleasure. It was to build a fort with, to be guarded by a carrot-nosed snowman and defended with hard-packed balls of winter fury. It was to slide down, wherever there was the slightest incline, and cardboard boxes could be procured for those of us without sleds.

The pleasures of snow lasted into our teens, not so much as adventure but as a brief retreat from drudgery. We listened hopefully to the radio in the kitchen for the weather report for those magic two words: Snow day!

For that small span, no rushing between classes, no last-minute check of homework, no drowsy study hall or hideous cafeteria food. Just freedom, to do anything or nothing, sweet for its serendipity, sad for its brevity.

Somewhere in our young adulthood, we began to experience the challenges of snow — the way it slows things down and rearranges schedules and turns simple travel into a nightmare. But they were challenges we gathered our resolve for and met steadfastly.

And if the challenge was big enough and our response touched with enough grace, a life experience was born that became a story ever larger with each telling, until it assumed mythical proportions. It’s like being in the military — we gripe and whine every minute of it, then spend the rest of our lives extolling its transformative virtues.

“Yeah, boy, the blizzard of ’78, just about killed me. My wife and I decided to walk the half-mile to my office, and we got turned around somehow, lost and with no sense of where we were for hours and hours. It was sheer luck that we didn’t freeze to death.”

The truth is that it was a couple of blocks, and we were disoriented for about 10 minutes. But what kind of story is that?

I was watching TV the other day, cursing under my breath as the meteorologist revised upward the total amount of snow expected, when I saw something that made me start reflecting on life’s snow journey, from the happy abandon of youth to the nervous worries of age.

It was a list of the schools that would be closed the next day, but I could tell that there would be no happiness in the announcement for some students, because right after many of the “snow day” listings was another bit of information: “e-learning day.”

Lord, what some of these students have gone through.

They get locked out of school for months on end, stuck in front of terminals for lessons their teachers don’t know how to get across, losing precious education and accruing mental health deficits. Then, they go back to school, but masked and distanced into isolation, perhaps having to listen to the adults argue about mandates and freedom.

Finally comes one day of blessed relief, a chance to be just a kid again, at least for a moment. But, no, kids, no joy for you. Back to that computer terminal.

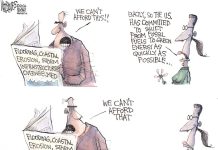

We – and I mean everyone, the people in charge during this pandemic and those of us who have enabled them – will have a lot to answer for in the way the response has been mishandled.

But one sin above all will stand out: We are making our children old before their time.