They were known by various names – the book women, the book ladies, the packsaddle librarians.

From 1935 to 1943, they rode through the hills of Depression-era Appalachia, hundreds of miles a week on difficult trails through sometimes awful weather, circulating a few books, magazines and greatly outdated newspapers to people living in isolated mountain cabins in areas where there were no libraries and few schools.

About 30 packhorse libraries reached between 100,000 and 600,000 people and also provided books for about 155 schools in the counties they served. The women were paid $28 a month by FDR’s Works Progress Administration and had to provide their own mounts – horses, mules, even donkeys. Sometimes they went by boat, and sometimes they walked.

And the women did something even more remarkable. They harvested knowledge as well as dispensing it. They collected recipes, folk remedies, local history lore, prayers and songs and other items and pasted them into scrapbooks, which they also circulated among their patrons. They even put together picture books for the children.

In 1956, Kentucky Rep. Carl D. Perkins, who had benefitted from the program as a teacher in Knott County, sponsored the Library Services Act, which provided the first federal appropriations for library service.

I was raised in Eastern Kentucky, but too late to benefit from the book women’s efforts. Until we were old enough for school, my brother and sister and I had to make do with the few books our parents could afford, which became worn and ragged and finally fell apart from overuse.

I’ve been an obsessive collector of books ever since. The overflow at my house is stacked up on one side of the staircase to the second floor, even though most of my reading these days is on an e-reader. One of the greatest discoveries in my Indiana teenage years was that the bookmobile came to within half a block of my house, delivering precious copies of science fiction by Robert Heinlein and Ray Bradbury and saving me long treks to the library.

In these days of the great political divide, we can’t seem to talk about anything without rancorous argument, even books, and lately especially books. We are at odds over what is in them, where they are, who has access to them, what use might be made of them.

We lose sight of the big picture. Books are the repository of human endeavor, the complete record of all we have done, what we have dreamed and where we have failed. Books are the reason humanity can advance, learning from what has gone before, not having to start all over each generation. Without books, we would still be scratching in the dirt and ignorant of the stars.

And until we all start trying to learn and grow by listening to podcasts and watching YouTube videos, books are still the key to knowledge. They are just as important today in urban Indiana as they were during the Depression in rural Appalachia. And sometimes, they can be just as difficult to access now as then.

Luckily, we have a modern equivalent of the book women, and her name is Dolly Parton. Bless her and the project she started in her home county in East Tennessee in 1995. Her Imagination Library gave each preschool child in the county one good quality, age-appropriate book a month, mailed directly to their home addresses.

The first book order sent out just over 1,700 books. But the program has since been replicated elsewhere, and today, the Imagination Library sends more than a million books a month to children around the world.

The participants include 56 providers in Indiana, cities and counties and school districts spread throughout the state. Gov. Holcomb has included $4.1 million in his budget proposal to make the program statewide for two years.

For a state that has $6 billion in reserves, it’s a puny percentage of a pittance. As a fiscal conservative, I normally look for ways to save money, but I can think of few initiatives for which such a great return can come from such a small investment.

At another time, in another context, we can put the books on our political agendas and argue away. But not now.

In fact, the only reason I can’t wholeheartedly endorse the governor’s plan is the fear that government might take something good and screw it up.

(Writer’s note: If you want to know more about the Depression-era Packhorse Library project, I strongly recommend “The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek,” Michele Richardson’s meticulously researched and engagingly written 2019 novel.)

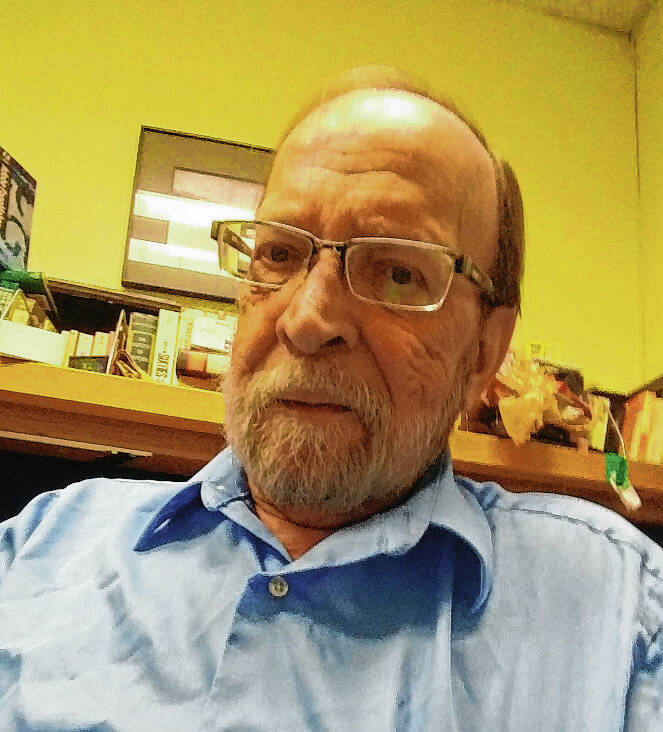

Leo Morris, columnist for The Indiana Policy Review, is winner of the Hoosier Press Association’s award for Best Editorial Writer. Morris, as opinion editor of the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, was named a finalist in editorial writing by the Pulitzer Prize committee. Contact him at [email protected].

Leo Morris, columnist for Indiana Policy Review, is winner of the Hoosier State Press Association’s award for best editorial writer. Morris, as opinion editor of the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, was named a finalist in editorial writing by the Pulitzer Prize committee. Contact him at [email protected]. Send comments to [email protected].