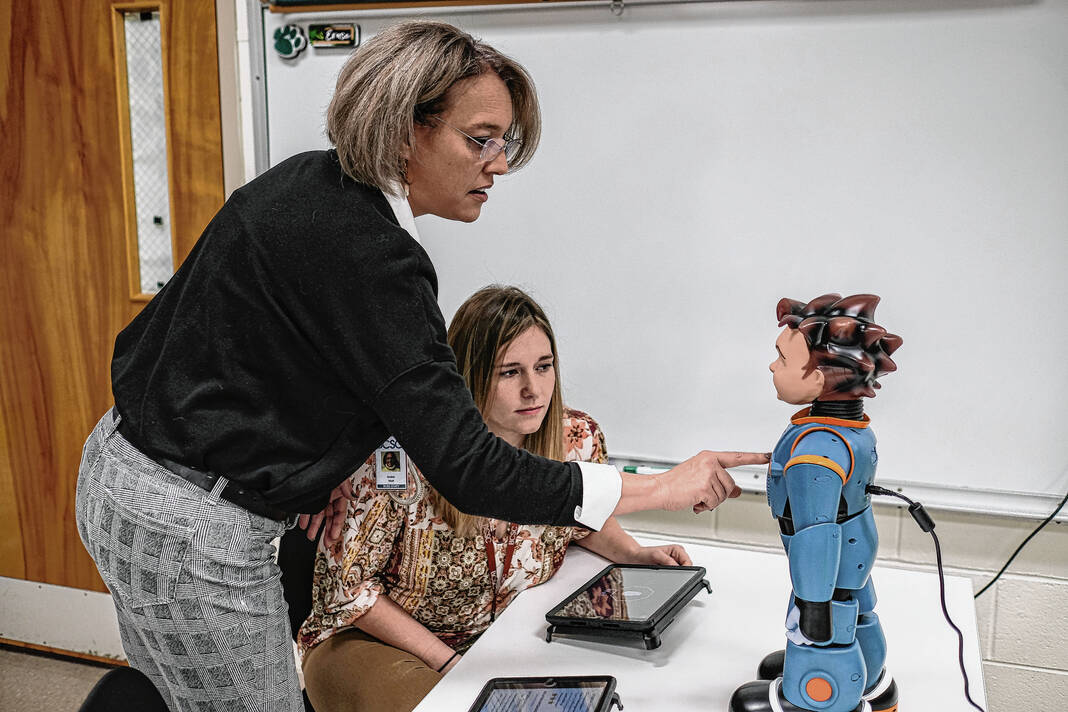

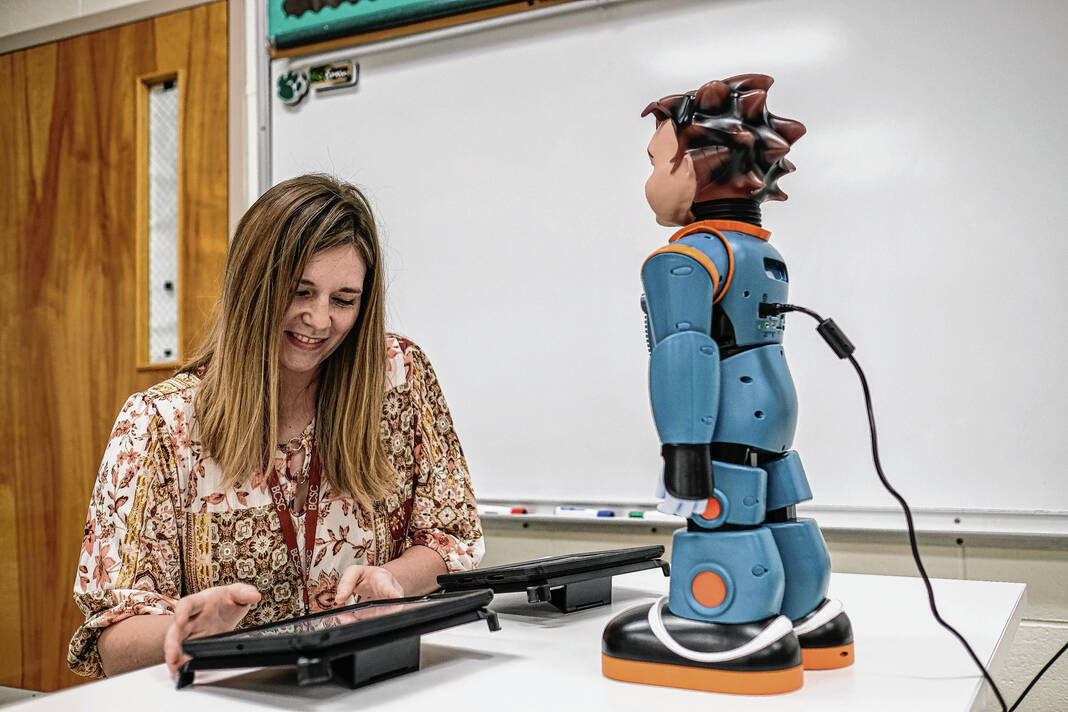

Mike Wolanin | The Republic State Reps. John Behning, from left, Ryan Lauer and State Sen. Greg Walker along with Bartholomew Consolidates School Corp. Superintendent Jim Roberts watch Registered Behavioral Technician Chelsea Smith, seated, and Bartholomew Consolidated School Corp. Autism Coordinator Amber Wolf, standing, and Ben Wyrick, a fifth grader at Rockcreek, demonstrate how they go through exercises with a robot named Milo that is designed to help children on the autism spectrum learn social skills at Rockcreek Elementary School in Columbus, Ind., Friday, Jan. 20, 2023.

Indiana legislators visited Rockcreek Elementary on Friday to meet with an unusual teacher — one that happens to be wired a little differently.

Sen. Greg Walker, R-Columbus, Rep. Ryan Lauer, R-Columbus and House Education Chairman Bob Behning, R-Indianapolis, visited the school to see a demonstration of Milo, a robot designed to help students with autism.

Autism coordinator Amber Wolf said Bartholomew Consolidated School Corp. was able to purchase five of these robots through a grant from the Indiana Department of Education. Rick Oslovar with RoboKind estimated that about 25 districts throughout the state are utilizing the program, with about 3,000 to 4,000 students participating.

Milo is a “facially-expressive humanoid robot designed to teach students on the autism spectrum social skills for life, according to RoboKind.

“From the beginning, we designed our robots to support and meet the needs of special educators as they guide their autistic students toward social-emotional mastery,” according to the company. “Among the many movements they make, each robot replicates most human facial expressions and speaks 20% slower than most people. The embedded chest screen displays core vocabulary and icons, an important evidence-based practice.”

BCSC has been rotating its five bots between its different elementary schools for about three months, said Wolf.

“They haven’t escaped or anything?” joked Lauer.

Far from starting any kind of robot uprising, Wolf said that Milo has helped students make significant progress. For instance, legislators were introduced to Ben Wyrick, a fifth grader who has been learning about greeting people from Milo.

Ben began by greeting each adult, learning their names, and shaking their hands. He then sat down for a lesson with Milo, who talked about how to say hello to different people and the phrases one might use, depending on the situation.

“We can greet by looking at someone’s face, smiling and saying hi,” the robot instructed.

Ben also used a tablet to watch a video about greetings and answer a question about what he’d learned.

He said that Milo has been “great” and has also helped him learn tools for calming down.

Wolf said that Ben’s time with Milo has led to “tremendous growth” both academically and socially.

The benefit of robots, said Oslovar, is that they provide consistency.

“They’re not judgmental,” he said. “A teacher will sometimes have a bad day. If Milo gets bit, he doesn’t care. He’s still going to be consistent, teach and do whatever.”

He added that some kids even like the robots so much that their parents will hear all about their new friend Milo, not realizing at first that the new friend is a mechanical companion.

Of course, Milo isn’t meant to be students’ only friend.

“That’s the goal, the generalization, trying to allow them to participate in all the other activities that the other kids do,” said Jon Gubera with RoboKind. “… The whole goal is to be able to have them integrate into society, like everybody else does. It’s just the way to get them there is a little bit different.”

Oslovar recalled one instance where a child had been non-verbal for eight years. After working with a robot, he was able to spend 20% of his time in a general education classroom, respond to a question from a newscaster and prepare for a birthday party.

“The student we’re looking at, he’s in fifth grade,” said Rockcreek Principal Jennifer Detmer, in regards to Ben. “So one more year, he goes into the middle school. We are a smaller school right now, but he’s going to a much larger building, and so he will have the skills to communicate and have conversation back and forth instead of just a one-way conversation.”

Walker commented that it almost seemed “counterintuitive” to use robots for this purpose, since it seems like some people turn to technology to avoid real-life interaction.

Gubera replied that many kids on the spectrum, including some individuals with autism who intern at RoboKind, have a “amazing analytical skills” and show a better response to digital interaction.

“It’s more concrete,” he said. “It’s not emotional. The biggest challenge they have is emotions fire off, and they don’t have the skills to manage their emotions. The robot is not emotional, right? It’s disarming. It’s digits. It’s ones and zeros, coding, right? So that is the catch — to them it makes more sense, because it’s maybe more like them. And then so that’s the breakthrough for them.”

He added that they’re not meant to “stay on the robot forever.” Milo is simply a tool for “bridging the gap” and helping with social-emotional skills so that students can transfer these to human interactions.

Legislators expressed interest in Milo, with Behning saying that although he’d seen the bot before, he was “super encouraged” to see the impact it has had on an actual student.

“Anything that helps Ben to have a better way to interact with his peers, I think, is important, that he’s in a mainstream setting,” said Walker. “I’m curious as to how the other children would respond or indicate what they’ve seen in Ben since the time he’s been able to use this tool.”

Lauer said that he was encouraged to this use of “innovative technologies” to help with education.

“We should be exploring all these kinds of options,” said Lauer.